Climate change litigation is on the rise. There are now more lawsuits challenging governments and corporations over a failure to act on environmental pledges or for making misleading claims.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

In 2017, 884 climate change cases were brought in 24 countries. By the end of 2020, that number had nearly doubled, with at least 1,550 cases filed in 38 countries – 39 including the European Union’s court system — 1,900 cases are ongoing or have been resolved.

Climate litigation has also become more successful. Cases with outcomes ‘favourable’ to climate action are in the majority, according to the Climate Change Laws of the World (CCLW) database, jointly run by the London School of Economics (LSE) and the Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment.

A report by the Network of Central Banks and Supervisors for Greening the Financial System (NGFS) found 2021 to be “an exceptional year” for climate-related litigation. It noted that supervisory authorities may not have, so far, fully recognised the impacts of such cases.

Now on the up, climate litigation has even inspired its own podcast. Damages which debuted last week, follows hundreds of active climate lawsuits around the world.

Some of the recent trends in climate litigation include cases that are “rights-based”. Violation of fundamental human rights, including the right to life, health, food, and water, are at the centre of such lawsuits.

Cases challenging the failures of governments to enforce their commitments on climate change mitigation and adaptation continue to grow, with 34 ‘systemic mitigation’ cases around the world, according to CCLW data.

While climate litigation continues to be concentrated in high-income countries, cases in the Global South are surging, with recent cases being registered in Colombia, India, Pakistan, Peru, the Philippines and South Africa.

In 2020, nineteen youth activists filed a complaint in the South Korean Constitutional Court alleging that insufficient action on climate change violates fundamental rights, including their rights to life and a clean environment.

South Korea-based environmental group, Solutions for Our Climate, however, believes that the increase in case volume has not been translated into impact.

Haewoong Jeon, who advises on litigation for the group, said that Asian activists, having seen how climate litigation in the United States and Europe have been successful, are now trying to take what they can from the victories and apply it to their own situation, including in South Korea. “However, it may still take time to see any key changes in climate litigation in Asia.”

“Asian courts have a more conservative view on climate change than European or American courts”.

Private sector in the dock

Cases are becoming more varied in nature — hitting out at private firms and financial actors, particularly as some of the more high-emitting sectors are not seen to be taking substantive action to reduce emissions or move towards net zero.

Courts are also seeing a diversity in the arguments to skewer climate offenders, including themes of greenwashing and fiduciary duty.

“Our focus has since diversified and expanded to climate finance, new domestic coal power plants, biomass power plants, greenwashing about a gas field,” Haewoong told Eco-Business.

Last year saw a global first for taking on corporate titans in the courtroom. Milieudefensie, the Dutch wing of Friends of the Earth, an international environmental coalition, achieved success in a court in the Netherlands which ordered Shell to cut its carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions by 45 per cent by 2030, on the grounds that the oil giant is violating human rights by contributing to global warming.

While the oil major is appealing the decision, Shell has nonetheless said that it will speed-up its planned transition to adhere to the judgement.

“Now that the courts are forcing Shell to take its responsibility in resolving the climate crisis, it is clear that other major emitters will now also have to take swift action to go green,” Milieudefensie director Donald Pols said at the time.

The environmental group demanded last month that 30 major polluters that have entities incorporated in the Netherlands, including BP, Shell, ExxonMobil, KLM, and Unilever, present a concrete and feasible climate plan within the next three months. The plan must detail how they intend to reduce their CO2 emissions by at least 45 per cent by 2030.

An increasing number of cases are being brought on the grounds of “climate-washing” where there is a gulf between the advertised performance of a company and climate action in reality.

Ambiguous advertising could give rise to climate litigation based on fraud, misrepresentation and consumer protection, according to a paper by LSE and the Grantham Research Institute.

A case filed by the Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility (ACCR) is challenging energy firm Santos and its claim that it will achieve net-zero emissions by 2040. The ACCR argues that Santos is deceptive as it is relying on carbon capture technology that does not exist or has not been disclosed.

It is the first lawsuit in Australia raising the issue of climate greenwashing against the oil and gas industry.

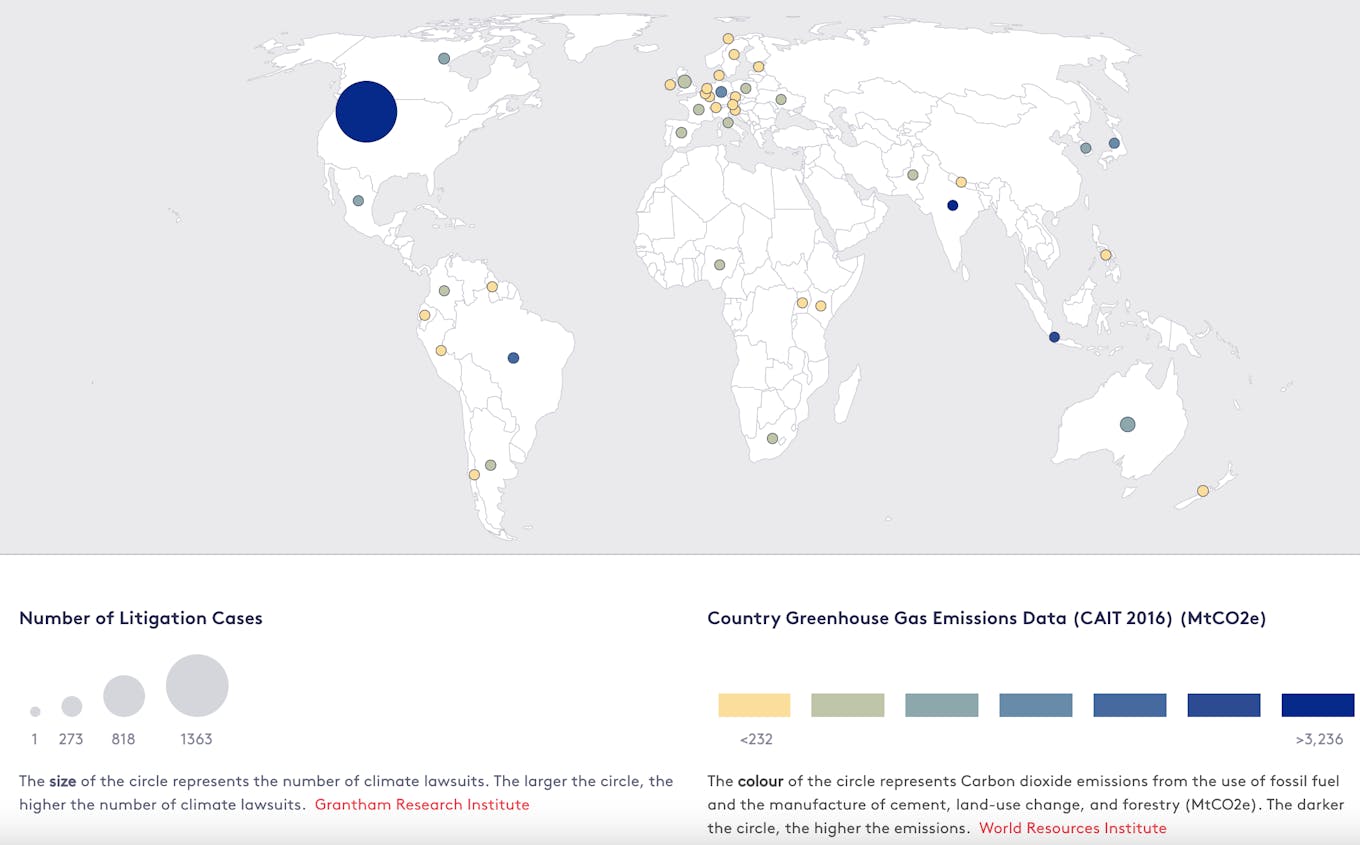

Number of climate litigation cases worldwide. Image: LSE and Grantham Research Institute on Climate Change and the Environment.

Meanwhile, product liability litigation, which has previously hit the tobacco industry for its concealment of the health effects of smoking, has inspired similar cases against major emitters of greenhouse gases.

Advertisements that represent gas as “clean” or “cleaner”, for example, may be perceived as misleading, according to a new report on climate litigation by the research firm, Climate Social Science Network (CSSN). Vehicle manufacturers and the transport sector are also under scrutiny for falsely advertising the environmental benefits of their products.

“There is huge scope for climate washing litigation, especially as government entities and corporates make net zero commitments,” said Benjamin Franta, who co-authored the CSSN report. “There are many examples of categories where we need to ensure that what is being said publicly is true and that we are safeguarding the integrity of communication around climate change.”

In their ads, Firstgas claimed: “New Zealand’s heading towards zero carbon so we’re ensuring our gas is going zero carbon too. You know what that means for you? Absolutely nothing. You can continue doing what you love. And help change the world, without changing too much of yours.” Image: Firstgas

A campaign group in New Zealand took issue with energy company Firstgas for advertising “zero carbon” gas, arguing that it was misleading and unsubstantiated. Lawyers for Climate Action said that Firstgas was relying on future technology and industry development that are not yet proven — which successfully resulted in the removal of the advert last July.

Cases regarding climate misinformation, so-called ‘climate-washing litigation’ are likely to increase, predicts Catherine Higham, coordinator for CCLW, particularly “as questions about the climate impacts of corporate activities across all sectors of the economy become more mainstream.”

What to watch

Climate litigation as “an activist strategy” is on the rise as claimants try to create public awareness around an issue to help pressure behavioural change in governments and multinationals. These cases may not win but might result in a broader societal shift.

“

As climate impacts continue to worsen, poorly adapted facilities may cause localised environmental damage which could lead to litigation.

Catherine Higham, coordinator for Climate Change Laws of the World

But not all strategic litigation is aligned with climate goals. Litigation can also be used to delay effective action on climate change, said Higham told Eco-Business.

Heavy polluters are attempting to seek compensation under international investment agreements for measures which might force companies to close existing fossil fuel plants or abandon already licensed exploration.

“There are thousands of these agreements around the world and the threat of such compensation claims has already been cited by some non-governmental organisations and media sources as a reason for the watering down of provisions in some legislation,” Higham said.

ExxonMobil in the United States is claiming that lawsuits against the company is a violation of the country’s constitution’s guarantees of free speech. It is pursuing legal action against more than a dozen California municipal officials. “These cases are very much designed to distract and intimidate litigants who are arguing for increased climate action,” according to Higham. Generally, these cases have not fared well in court, Franta added.

Other areas to watch in the future include value chain litigation where claimants seek to hold companies responsible for acts and omissions in their value and/or supply chains. This is particularly pertinent in Asia—where global companies often have their lion’s share of production and manufacturing.

“As supply chains are global, it will be difficult for many companies to hide from litigation and civil society pressure,” said Gerard Rijk, analyst at research non-profit, Profundo. “The European Union is working on supply chain due diligence regulation, and companies with headquarters and activities in Europe will be confronted with this, in their global activities.”

Insufficient attention to supply chain resilience could also expose directors and officers to potential claims.

“An area that might see growth is cases concerning corporate failures to ensure that physical assets such as factories and mines are well adapted to climate change. As climate impacts continue to worsen, poorly adapted facilities may cause localised environmental damage which could lead to litigation,” Higham said.

Other cases might look to challenge government support to the fossil fuel industry—through subsidies or tax relief—and could focus on the distribution of the burdens associated with action, which may be classed as ‘just transition’ cases.

Persistence in Asian courts will hinge on success of climate cases, said Haewoong. “If seasoned activists and experienced lawyers fail to change the attitude of the court, the young activists who have been fighting to avert climate change may lose steam on climate litigation.”