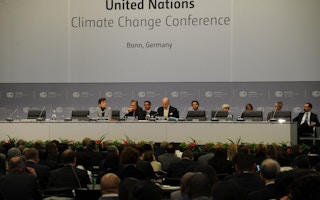

The latest round of United Nations climate negotiations showed why the UNFCCC process is essential to the global response to climate change – and why it must be complemented by action from businesses, cities and regions. The preparatory meeting for December’s Paris climate change summit which ended on Thursday in Bonn, Germany saw important progress on elements of the United Nations climate regime, alongside frustrations at the pace of negotiations. The central task before national negotiators – to agree a text that will form the basis for a global climate deal at COP21 – remains daunting.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

Nevertheless, after two weeks marked by a G7 commitment to decarbonize the global economy, the economic and political shift in favor of climate action in the years since 2009’s Copenhagen summit has never been more clear. As participants widely acknowledged, the diplomats are playing catch-up.

Preparing for Paris

“

The agreement on forest protection in developing countries showed that the process can deliver breakthroughs when negotiators are authorized by their governments to find common ground to implement higher-level decisions.

The negotiation for a 2015 climate deal has two tracks – the first on the design of a climate agreement to come into effect from 2020 and the second on enhancing pre-2020 climate action. In Bonn, negotiators worked on streamlining the ninety pages of existing draft text of the first negotiating track – essentially a collection of national proposals. The work of twelve negotiating streams on sections of the text (such as mitigation, finance and technology) resulted in a new paper only slightly shorter than the previous version. The co-chairs of the negotiation have been asked to prepare an updated text by late July, ahead of the next round of talks in August.

While the focus on consolidating the text prompted concerns over lack of progress on the substance of the Paris outcome, the fact is that the delegates in Bonn were not empowered to strike compromises on the overall design of the climate regime. For example, multiple negotiating parties and observers have criticized the ongoing uncertainty over the role of market mechanisms under a Paris deal. According to Lambert Schneider, who chairs the board of the UNFCCC’s existing market mechanism, the Clean Development Mechanism, this lack of clarity is a ‘major barrier’ to future projects. The CDM has mobilized at least $150 billion in private investment, but its latest annual report shows that the number of new projects has collapsed. However, the role of market mechanisms is a political question that will be negotiated by more senior government representatives in Paris.

In contrast, the agreement on forest protection in developing countries showed that the process can deliver breakthroughs when negotiators are authorized by their governments to find common ground to implement higher-level decisions. The decisions on reporting requirements for projects to reduce emissions from deforestation and forest degradation, or REDD+, cover: safeguards for transparent forest governance, indigenous rights, conservation of biodiversity and other matters; the role of non-market-based policy approaches to forest protection; and the non-carbon benefits of REDD+ activities. These decisions, which capped a decade of REDD+ negotiations in the UNFCCC, set the stage for greater use of REDD+ as a tool for climate change mitigation. This would be particularly significant for countries such as Indonesia, where an estimated 74 percent of greenhouse gas emissions come from land use, land use change, forestry and peatlands.

Momentum from business and subnational governments

“

The growth of initiatives by public and private organizations complements the UN climate process which, by giving a voice to all nations including those most vulnerable to climate change, has unique legitimacy.

Alongside the intergovernmental negotiations, the Bonn session provided multiple demonstrations of what Rosa Morales, representing the outgoing Peruvian presidency of the climate conference, has called ‘an exponential growth of climate action’. The Technical Expert Meeting on renewable energy examined the dissemination of renewables through the markets, the UN system and other international organizations. A separate session heard that East Asia is becoming increasingly important to the development of clean energy, with China and South Korea filing the most patents for biofuels, solar and wind energy in recent years.

In addition, a ‘Climate Action Fair’ showcased the climate programs of business and subnational governments, such as IKEA’s pledge to invest 1 billion euros in renewable energy and support for climate-vulnerable communities. There are indications that the diverse initiatives of subnational governments, businesses and investors could have a significant impact. According to a UN Environment Programme report released last week, programs to cut emissions by cities, regions and businesses could prevent approximately 1.8 gigatons of emissions in 2020.

The growth of initiatives by public and private organizations complements the UN climate process which, by giving a voice to all nations including those most vulnerable to climate change, has unique legitimacy. Indeed, the draft outcomes document for September’s UN summit, where the Sustainable Development Goals will be adopted, affirms that the UNFCCC is the ‘primary’ forum for negotiating the global climate response. But while non-state climate initiatives are no substitute for national commitments, they should be seen as force multipliers for intergovernmental agreements that put more ambitious targets within reach. Recognizing this, the UNFCCC process has changed, becoming more inclusive of businesses and subnational governments, notably through the Lima-Paris Action Agenda.

Hopeful signs for a low-carbon transition

At the beginning of the June UNFCCC session, twenty negotiating days were left prior to the Paris summit. Now, ten remain. Speaking in Bonn, COP21 special representative Laurence Tubiana noted that the treaties of Westphalia took two years to negotiate; the officials meeting in Paris will have two weeks. The tight timeframe places pressure on negotiators, with no guarantee that major sticking points will be addressed. But it is also true that the UN climate regime has become an iterative process rather than a quest for a once-and-for-all global deal. In this context, decision-makers will continue to increase the ambition of mitigation and adaptation.

Also meeting in Germany, the G7 group of major industrialized countries came out in support of global emissions reductions of up to seventy percent by 2050 from 2010 levels and the ‘decarbonisation of the global economy’ during this century. G7 leaders committed to developing ‘long-term’ low-carbon strategies for their own countries and the extension of insurance against the effects of climate change to 400 million people in climate-vulnerable countries. This Thursday, Pope Francis is expected to issue an encyclical calling for climate action to protect the world’s poor. These acts of leadership, coupled with indicators such as the International Energy Agency’s report that global economic growth may have begun to uncouple from energy-related emissions in 2014, point to an accelerating global response to climate change. But if the direction of travel seems clear, the Paris deal will play a crucial role in determining the pace.

Stephen Minas is a research fellow at the Transnational Law Institute, King’s College London. This piece was written exclusively for Eco-Business.