Environmental groups have cautiously welcomed palm oil giant Wilmar’s two-year update on its zero-deforestation policy, saying that while the firm has achieved progress on making its operations more traceable and transparent, major improvements are still needed in aspects such as holding suppliers accountable for deforestation and resolving conflict with communities.

In its Policy Progress Report 2015, unveiled on Thursday in Davos, Switzerland at the sidelines of the World Economic Forum meeting, Wilmar said it has made “significant progress” towards fulfilling the ‘no deforestation, no peat, no exploitation’ promise it made in December 2013.

For example, it has increased traceability within its supply chain, developed a new strategy for developing region-specific solution to policy violations by suppliers, and has helped smallholder farmers on its concessions grow palm oil in more sustainable ways.

Jeremy Goon, chief sustainability officer, Wilmar, said in a statement: “I am proud of the progress our team has achieved this far and heartened that Wilmar’s integrated policy has kick-started change in the palm oil industry”.

When Wilmar announced its zero deforestation policy in 2013, it was among the first players in the industry to commit to ending forest clearance, peatland development, and human rights abuses. Since then, many of the biggest names in the sector, including Musim Mas, Cargill, and Astra Agro Lestari, have made similar commitments.

Industry-led initiatives on sustainable palm oil, such as the Indonesian Palm Oil Pledge – a sustainability commitment by palm oil majors such as Wilmar, Cargill and Asian Agri, and the country’s chamber for commerce – have also been set up since then.

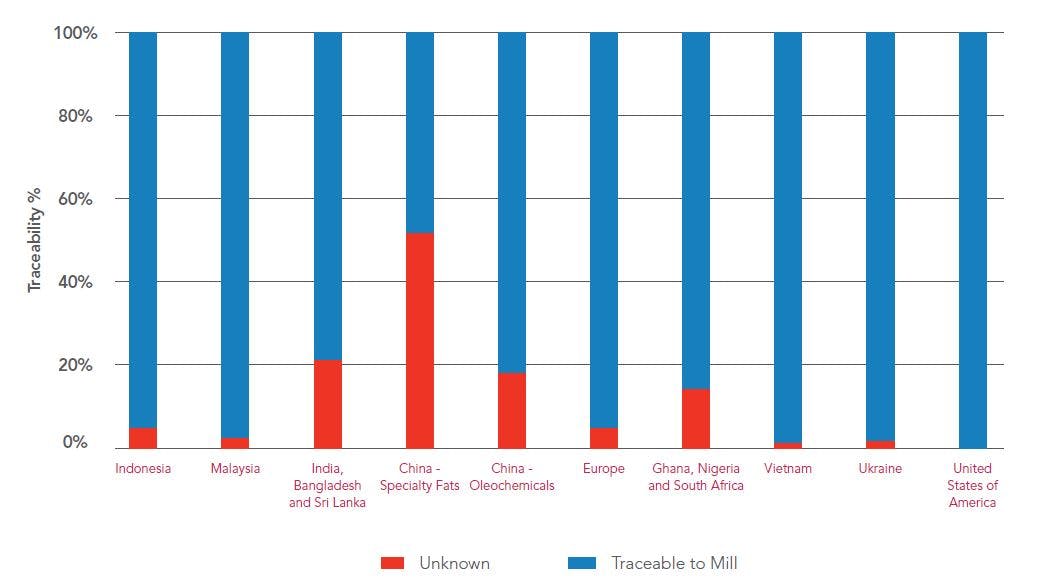

Traceability of Wilmar operations globally from October 2014 to September 2015. Image: Wilmar

In its latest report, the firm - which is the world’s largest palm oil processor - reported that in a majority of its operations in Indonesia, Malaysia, Europe and United States, the palm oil is traceable back to the mill from where it was sourced.

The company has also begun to track its palm oil back to the plantation where the fresh fruit bunches were grown and has released a detailed sourcing map for one of its mills in Sabah, Malaysia. It aims to eventually do this for all its third-party suppliers.

Traceability to plantations is a more detailed way of tracking palm oil than tracing to mills, as it enables manufacturers and palm oil buyers to ascertain where a specific batch of palm oil was grown. This allows them to verify whether it was grown on illegally deforestated land or conversely, a plantation certified sustainable by industry association Roundtable on Sustainable Palm Oil.

Also in the works is an initiative, “Aggregator Refinery Transformation”, to ensure that all the 1,000 mills which supply to Wilmar comply with its rules for environmentally and socially responsible cultivation.

Based on assessments in each region it operates in, Wilmar identifies issues common to that area and outlines the best practices that all mills and growers have to should to. It also works with non-government organisations to monitor its suppliers and identify potential violations.

To improve its transparency and accountability to stakeholders, Wilmar will remove the login requirements currently required on its online sustainability dashboard, and make it open to the public by the first quarter of this year.

The company in its report also shared plans to eliminate forest burning on its concessions, end the exploitation of workers, and do more to empower smallholders, such as helping them access affordable fertiliser and building traceability systems they can use.

Despite these measures, Wilmar’s Goon acknowledged that much remains to be done, including developing “a clear means to measure and track the progress of sustainability commitments to assess (the policy’s) effectiveness in reducing actual deforestation”.

Green groups also pointed out that Wilmar needs to do more to assure stakeholders that its suppliers are not illegally burning or clearing forests, and take actions such as cutting them out of the supply chain if they are caught doing so.

Last July, forest fires from Indonesia blanketed Southeast Asia in a toxic smog for months, causing record-breaking air pollution levels. Many green groups accused the palm oil industry of contributing to the crisis by burning land to make way for new plantations.

Annisa Rahmawati, forest campaigner, Greenpeace Indonesia, noted in a statement that Wilmar’s policy has not delivered the transformative change it promised in 2013.

“Deforestation in Indonesia is accelerating and Wilmar is unable to prove that its suppliers are not responsible…Nor has it made significant progress towards eliminating social conflict within its supply chain,” she said.

Social conflict may refer to instances where community land is taken from them without free, prior, and informed consent, or workers’ human and labour rights are violated, among other things.

The company in its report acknowledged that while it carries out field assessments to ensure that its suppliers behave responsibly, the sheer scale of its global operations - it accounts for about 45 per cent of the world’s globally traded palm oil- means that some violations go undetected.

To plug this gap, Wilmar launched a “Grievance Procedure” a year ago, which records and investigates reports from stakeholders about potential policy breaches. This platform is an industry first, and the company has investigated 19 grievances to date, said Wilmar.

Other experts noted that despite its shortcomings, Wilmar has led a sea change in how the industry operates.

Glenn Hurowitz, senior fellow, Center for International Policy, praised Wilmar’s work as the beginning of a revolution that breaks the link between palm oil and deforestation, but echoed Rahmawati’s point that it wasn’t clear if suppliers were actually reducing deforestation.

It also did not communicate whether there are consequences for suppliers who violate Wilmar’s rules, he noted.

But this in an industry-wide problem, said Hurowitz, pointing that no company is fully transparent about its supply chain. “This transparency gap should be an area of major focus for the industry in 2016, and Wilmar can once again lead the way,” he said.

Scott Paul, head of the Forest Heroes campaign, a global coalition of forest activists, said that while Wilmar can do more to accelerate progress on its policy, “the fact is they’re still perhaps the most forward-looking commodity company in the world,” he noted.

“The supply chain revolution is a work in progress, but it has begun”, he added.