A huge portion of Indonesia’s fast-growing palm oil sector could become obsolete in order to rein in greenhouse gas emissions, predicts a report by Orbitas, a climate transition risk think tank.

To continue reading, subscribe to Eco‑Business.

There's something for everyone. We offer a range of subscription plans.

- Access our stories and receive our Insights Weekly newsletter with the free EB Member plan.

- Unlock unlimited access to our content and archive with EB Circle.

- Publish your content with EB Premium.

More than two thirds (76 per cent) of unplanted concessions in Indonesia and 15 per cent of the country’s current concessions, including land farmed by smallholders, could be stranded assets by 2040, as efforts to end tropical deforestation ramp-up in a bid to comply with the Paris Agreement to slash carbon emissions to stave off climate change.

Indonesia is the world’s largest palm oil producer, responsible for 72 per cent of a US$43 billion industry. The sector has grown rapidly in recent years at the expense of forests and carbon-rich peatlands; from 2001 to 2019, 27 million hectares of forests were lost in provinces dominated by palm oil production. Indonesia is the world’s fifth largest emitter of greenhouse gases, mainly due to deforestation and peatland fires associated with clearing shrubs and trees for agriculture.

Commitments made by the Indonesian government to reduce emissions and a national ban on palm oil expansion, together with the recent report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change that calls for a complete halt on tropical deforestation, are piling pressure on palm oil firms to reduce their climate impact.

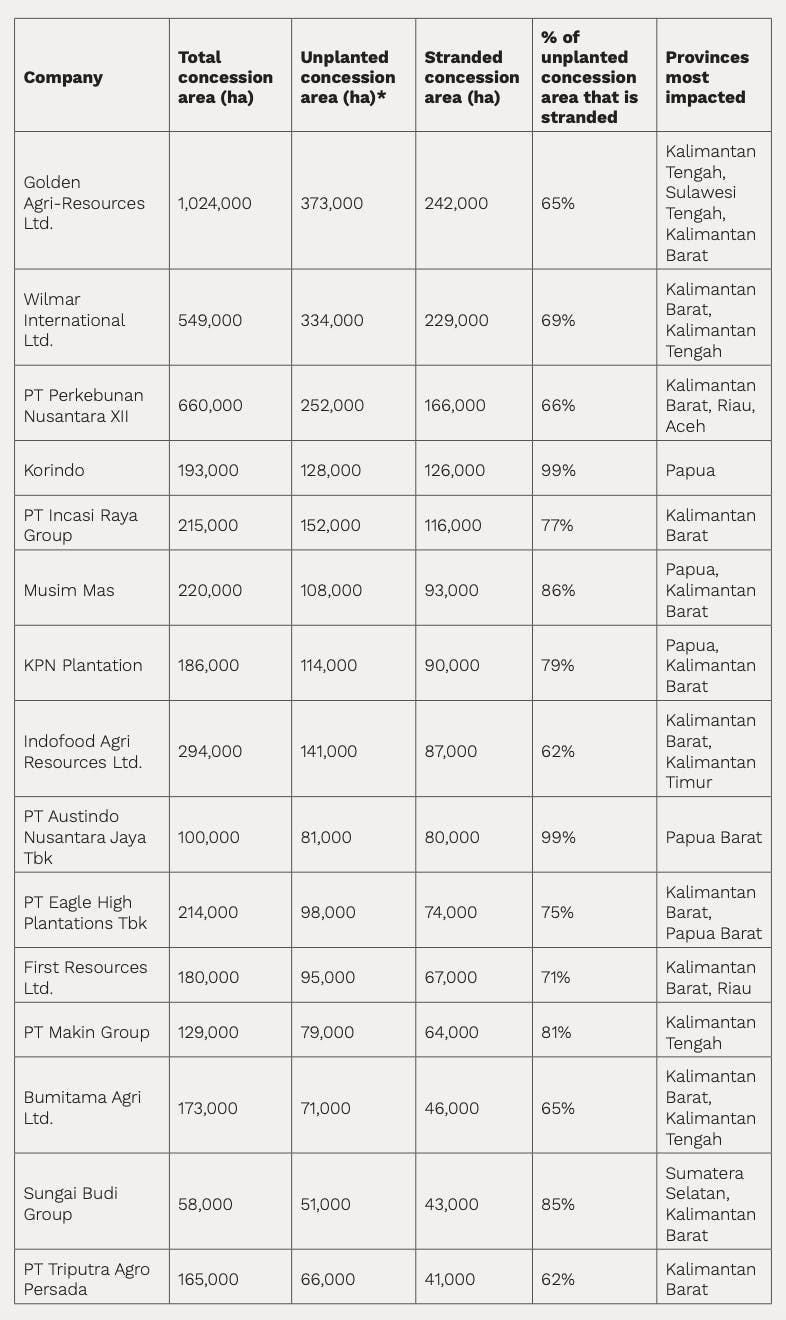

Palm oil companies and stranded asset risk. The figures in the above table are roughly representative of the best available data for 2015. Because of possible temporal and spatial discrepancies in 2015 concessions map data versus current planted palm maps, the current number of hectares at risk of becoming stranded assets may have changed. Source: Orbitas

According to Orbitas’s report, titled Indonesian palm oil sector facing stranded asset risk, palm oil firms with concessions on high carbon stock forests or high conservation value lands will have to write-off 9.2 million hectares of concessions that cannot be developed under sustainability commitments.

Sixteen major palm oil producers and refiners operating in Indonesia have no deforestation, no peat, no exploitation (NDPE) pledges in place, including Wilmar, the world’s largest palm oil trader, Golden Agri-Resources (GAR) and Musim Mas. GAR has the largest potential stranded asset area.

Two companies are highlighted as particularly vulnerable to climate transition risk, and both have operations focused in biodiverse Papua: PT Austindo Nusantara Jaya and Korindo. The latter firm was recently expelled from eco-label body Forest Stewardship Council for alleged human rights violations and deforestation in Papua.

Under the most stringent of climate action scenarios, Indonesia’s smallholder farmers will be affected by stranded asset risk, if they’re bound by the same no-deforestation rules as industrial firms.

The sector is already under pressure to ramp up climate action. In the recent years, Norway’s US$1 trillion sovereign wealth fund divested from 33 palm oil companies over deforestation concerns, PepsiCo and Nestle severed ties with Indonesian palm oil producer Indofood, and the European Union is phasing out palm oil in biodiesel because of the crop’s environmental impact.

Indonesia will continue to face increasing international pressure and incentives, such as carbon border tax adjustments, to reduce deforestation that will affect the growth of country’s powerful palm oil companies, Orbitas’s report suggests.

Growing by not expanding

Orbitas managing director Mark Kenber commented that climate concerns were already making deforestation in the palm oil sector uncompetitive, and firms that take climate transition risks seriously would continue to see growth.

The price of palm oil is projected to rise by 29 per cent by 2040, and restrictions on land use will boost revenue for companies that have strong climate policies in place that rule out deforestation in their concessions, the report finds. Higher land costs will force companies to use their land more efficiently, switch to technologies that drive up yield and rein in greenhouse gas emissions from fertiliser, diesel fuel use, and mill waste.

Financiers, the report suggests, should avoid investing in firms that have concession lands in areas of high conservation value, have weak NDPE policies, and business models that rely on land expansion.

Big producers and financiers also need to provide more support to smallholders, which produce 40 per cent of supply in Indonesia and are widely blamed for more recent deforestation, the report recommends.