The rise of primary energy use and CO2 emissions over four decades across 70 countries is not closely correlated with increases in life expectancy, a new study finds.

This suggests that increased fossil fuel use is not a key determinant of increased life expectancy, the lead author tells Carbon Brief.

The analysis finds that increased access to electricity in the home was much more closely associated with a longer life expectancy over the 40-year study period.

However, increases in access to home electricity were not highly correlated with increases in CO2 emissions, the study notes – suggesting that fossil fuels are not fundamental to access.

It is important to note, however, that there are limitations to using coarse indicators, such as primary energy use and life expectancy, to infer relationships between fossil fuel use and health and wellbeing, another scientist tells Carbon Brief.

Fossil fix?

Tackling climate change requires countries to rapidly transition away from burning fossil fuels.

In response to calls for action, some commentators have argued that using more fossil fuels can bring about increases in the health and wellbeing of populations – and that, because of this, developing nations should not be discouraged from using them.

The new study, published in Environmental Research Letters, addresses this claim. [For technical reasons, the journal has not yet been able to publish the study as planned.]

It finds that, over time, there is no strong association between increased life expectancy and fossil fuel use, explains lead author Prof Julia Steinberger, an ecology economist from the University of Leeds. She tells Carbon Brief:

“I was really, really shocked to see how little the increases in CO2 emissions and primary energy [use] could account for increases in life expectancy. I thought, by fluke, they would account for more because they’ve been growing tremendously all over the world.”

Patterns of change

For her analysis, Steinberger and colleagues looked at changes in several key per-capita metrics from 1971-2014 across 70 countries. (The authors chose to use every country which offered all the data required for the analysis. Together these countries represent 80 per cent of the global population.)

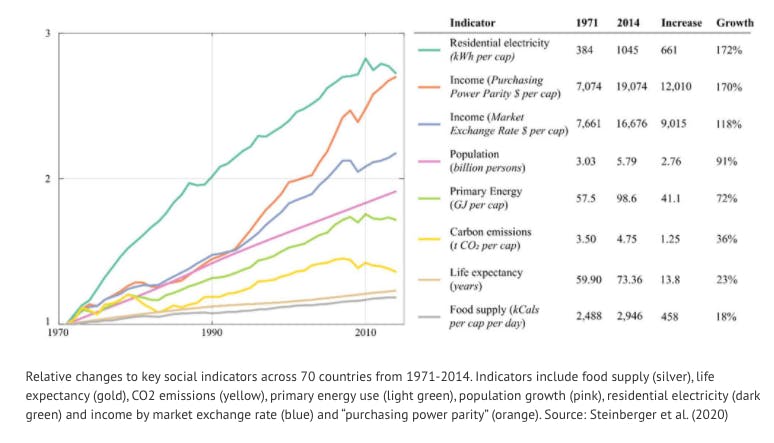

The chart below shows the changes in these metrics, which include food supply (silver), life expectancy (gold), CO2 emissions (yellow), primary energy use (light green), population growth (pink), residential electricity (dark green) and income by market exchange rate (blue) and “purchasing power parity” – a domestic purchasing metric that also considers the relative cost of living and inflation rates in different countries (orange).

(“Primary energy” is a measure of all the energy present at the point of extraction for fossil fuels or generation for renewables.)

The chart shows how residential electricity and purchasing power parity have increased the most rapidly out of all the indicators.

The researchers used a new analysis method, called “functional dynamic composition”, which involves using a set of equations to examine to what degree changes in one metric were linked to changes in another. This means the authors were able to measure correlations between different metrics, but they were not able to detect causal links.

For example, they looked at how closely increases in per-capita CO2 emissions were linked to increases in life expectancy. “We use CO2 emissions as an indicator, but really they are a proxy for fossil fuel use,” says Steinberger.

They find that increases in per-capita CO2 emissions and primary energy use were both linked to around a quarter of the increase in life expectancy. (Over the study period, average life expectancy increased by 14 years across the studied countries.)

By contrast, increases in residential electricity were tied to more than half of the increase in life expectancy, the study finds. Steinberger explains:

“It might be that residential electricity is a good proxy for other things that matter and in itself doesn’t matter very much. But I can think of very good reasons why residential electricity matters a lot in allowing people to live healthy decent lives.”

For example, having access to electricity in the home allows people to refrigerate food, stay in contact using the internet and forgo the use of wood and charcoal-burning stoves, which can negatively affect health, she adds.

The authors also studied the links between increases in residential electricity access and increases in CO2 emissions.

They find that increases in CO2 emissions were only linked to 36 per cent of the increases in residential energy, suggesting fossil fuels are not key for the provision of home electricity.

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.