The results come from a study looking at how various interventions could cut emissions from Germany’s meat industry. However, it is likely that the findings hold relevance for other countries, a study author tells Carbon Brief.

The single most effective way to reduce meat emissions would be to eat less of it, the analysis adds. It finds that halving meat consumption could reduce Germany’s meat emissions by 32 per cent, when compared to levels observed in 2016.

Further savings could be made by eliminating household meat waste and by improving the efficiency of animal-feed production, the results show.

Hard to swallow

Eating meat is a major driver of climate change. Rearing livestock accounts for around 14.5 per cent of global greenhouse gas emissions, with beef production responsible for just under half of this figure.

Many studies have found that eating less meat or switching to a vegetarian or vegan diet could greatly reduce emissions from the livestock sector.

The new study, published in Environmental Science and Technology, looks at how meat emissions could be reduced by a wide range of interventions, including changes to diet, the elimination of food waste and the introduction of more efficient animal rearing.

The analysis focuses on Germany, the largest meat producer in the European Union.

Average meat consumption in Germany fell by 12.5 per cent from 1990 to 2016, largely as a result of growing interest in vegetarian and vegan diets. However, Germans still eat twice as much meat as the world’s average person.

The study tracks emissions from every stage of the German meat industry, from animal rearing to when meat is eaten at home or in a restaurant.

It then uses modelling to explore how a range of interventions could help to reduce the meat sector’s emissions by 2050, when compared to levels in 2016.

The findings show there is “tremendous potential” for reducing emissions from the meat sector, says study author Prof Gang Liu, a researcher at the University of Southern Denmark. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Diet structure change, either by reducing meat consumption or substituting meat with offal, showed the highest emissions reduction potential. However, eliminating meat waste in retailing and consumption, and byproducts from slaughtering and processing, were found to have profound effect on emissions reduction as well.”

If a combination of these measures were pursued, Germany’s meat industry could cut its overall emissions by up to 43 per cent, when compared to 2016 levels, the research finds.

Slice by slice

The analysis finds that most of Germany’s meat emissions come from livestock production.

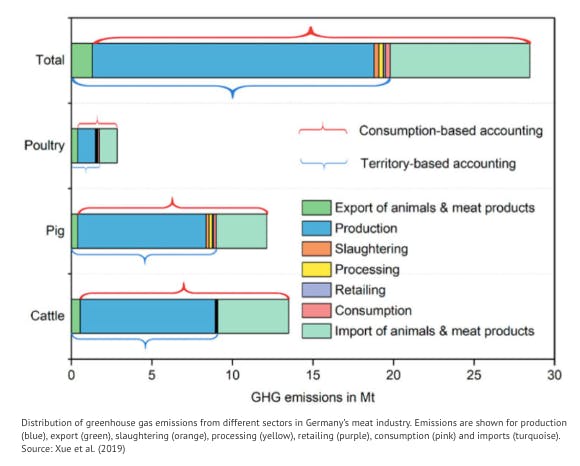

The chart below, which is taken from the paper, shows the distribution of greenhouse gas emissions from different sectors in the meat supply chain. Emissions are shown for production (blue), exports (green), slaughtering (orange), processing of meat (yellow), retailing (purple), consumption (pink) and imports (turquoise).

The production process is heavily polluting because rearing animals causes the release of methane, a greenhouse gas that is 34 times more potent than CO2 over a 100-year period. Methane is released when cattle belch and produce manure.

The import of live animals and meat products from other countries also makes a sizeable contribution to Germany’s meat emissions. One reason for this is that imports require the use of polluting transport.

Wasting away

The authors also examined how various interventions could help to reduce Germany’s meat emissions by 2050, when compared to levels observed in 2016.

The findings show that the single most effective way to reduce livestock emissions would be to eat less meat. The authors find that, if Germans halved their meat consumption and replaced the lost protein with plant-based sources, emissions would fall by 32 per cent by 2050, when compared to 2016 levels.

However, several other measures, such as eating more offal and eliminating food waste, could also help to reduce Germany’s meat emissions.

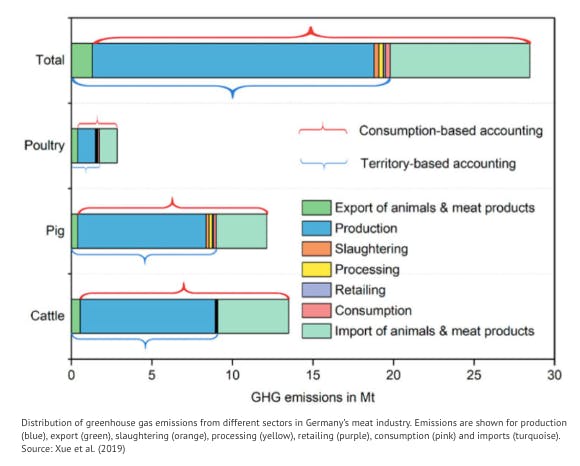

The chart below shows how various interventions could lead to a percentage decrease in meat emissions by 2050, when compared to 2016.

The research finds that eating more offal could cause meat emissions to fall by 14 per cent. This scenario assumes that offal consumption increases by 50 per cent by 2050. This would require people to include offal in a meal “once or twice a week”, Liu says.

If people chose to eat more offal, fewer animals would need to be reared overall, he adds. This fall in overall meat consumption explains why emissions would fall. (Currently, a lot of offal and animal waste is used for pet food and various industrial processes.)

Another scenario finds that a 20 per cent reduction in the by-products created in the meat slaughtering and processing stages could cause emissions to fall by 11 per cent, when compared to 2016 levels. This could be achieved by using more precise techniques for meat cutting, ensuring less of it is wasted, the authors say in their research paper.

An alternative way of cutting emissions would be to substitute beef for poultry or pork, which produce less emissions per portion, the authors say. This scenario assumes that substitutions cause beef production to fall by 25 per cent. This would result in an emissions reduction of 7 per cent, the study finds.

Chewing the fat

The results suggest that, if all interventions were pursued in tandem, the German meat sector could reduce its overall emissions by 43 per cent.

This level of reduction would “not be sufficient” for keeping global warming at 1.5C above pre-industrial levels – the goal of the Paris Agreement, Liu concedes. He tells Carbon Brief:

“We know that achieving the 1.5C target requires radical change in all sectors, including the agrifood sector. In many cases, a 75-100 per cent reduction of emissions and negative emissions solutions are needed. [But] we have to be realistic, we cannot turn the whole or even most of the world population to vegetarians. Meat eating will continue.”

The findings show how using the “entire carcass” of an animal – sometimes characterised as “nose-to-tail eating” – could be key for climate mitigation, says Prof Tim Benton, a food systems and climate change researcher from the University of Leedswho was not involved in the study. He tells Carbon Brief:

“While there has been a lot of discussion about the mitigation potentials of changing agriculture and diets, relatively little attention has been given to the supply chain between agriculture and consumption. This study shows that there are very significant inefficiencies in the meat supply chain that can, to some extent, offset some of the environmental issues associated with primary production.”

This story was published with permission from Carbon Brief.