Covid-19 is one of countless emerging infectious diseases that are zoonotic, meaning they originate in animals. About 75 per cent of emerging infectious diseases are zoonotic, accounting for billions of illnesses and millions of deaths annually across the globe.

When these diseases spill over to humans, the cause frequently is human behaviors, including habitat destruction and the multibillion-dollar international wildlife trade – the latter being the suspected source of the novel coronavirus.

The Covid-19 pandemic has forced governments to impose severe restrictions, such as social distancing, that will have massive economic costs. But there has been less discussion about identifying and changing behaviors that contribute to the emergence of zoonotic diseases. As a conservation biologist, I believe this outbreak demonstrates the urgent need to end the global wildlife trade.

Markets for disease

As many Americans now know, the Covid-19 coronavirus is one of a family of coronaviruses commonly found in bats. It is suspected to have passed through a mammal, perhaps pangolins – the most-trafficked animal on the planet – before jumping to humans.

The virus’s spillover to humans is believed to have occurred in a so-called wet market in China. At these markets, live, wild-caught animals, farm-raised wild species and livestock frequently intermingle in conditions that are unsanitary and highly stressful for the animals. These circumstances are ripe for infection and spillover.

The current outbreak is just the latest example of viruses jumping from animals to humans. HIV is perhaps the most infamous example: It originated from chimps in central Africa and still kills hundreds of thousands of people annually. It likely jumped to humans through consumption of bushmeat, or meat from wildlife, which is also the likely origin of several Ebola oubreaks. PREDICT, a US-funded nonprofit, suggests there are thousands of viral species circulating in birds and mammals that pose a direct risk to humans.

Decimating wildlife and humans

Trade in wildlife has decimated populations and species for millennia and is one of the five key drivers of wildlife declines. People hunt and deal in animals and animal parts for food, medicine and other uses. This commerce has an estimated value of US$18 billion annually just in China, which is believed to be the largest market globally for such products.

My own work focuses on African and Asian elephants, which are severely threatened by the wildlife trade. Demand for elephant ivory has caused the deaths of more than 100,000 elephants in the last 15 years.

Conservationists have been working for years to end the wildlife trade or enforce strict regulations to ensure that it is conducted in ways that do not threaten species’ survival. Initially, the focus was on stemming the decline of threatened species. But today it is evident that this trade also harms humans.

For example, conservation organisations estimate that more than 100 rangers are killed protecting wildlife every year, often by poachers and armed militias targeting high-value species such as rhinos and elephants. Violence associated with the wildlife trade affects local communities, which typically are poor and rural.

The wildlife trade’s disease implications have received less popular attention over the past decade. This may be because bushmeat trade and consumption targets less-charismatic species, provides a key protein source in some communities and is a driver of economic activity in some remote rural areas.

“

Terminating the damaging and dangerous trade in wildlife will require concerted global pressure on the governments that allow it, plus internal campaigns to help end the demand that drives such trade.

Will China follow through?

In China, wild animal sales and consumption are deeply embedded culturally and represent an influential economic sector. Chinese authorities see them as a key revenue generator for impoverished rural communities, and have promoted national policies that encourage the trade despite its risks.

In 2002-2003, severe acute respiratory syndrome, or SARS – a disease caused by a zoonotic coronavirus transmitted through live wildlife markets – emerged in China and spread to 26 countries. Then as now, bats were a likely source.

In response, the Chinese government enacted strict regulations designed to end wildlife trade and its associated risks. But policies later were weakened under cultural and economic pressure.

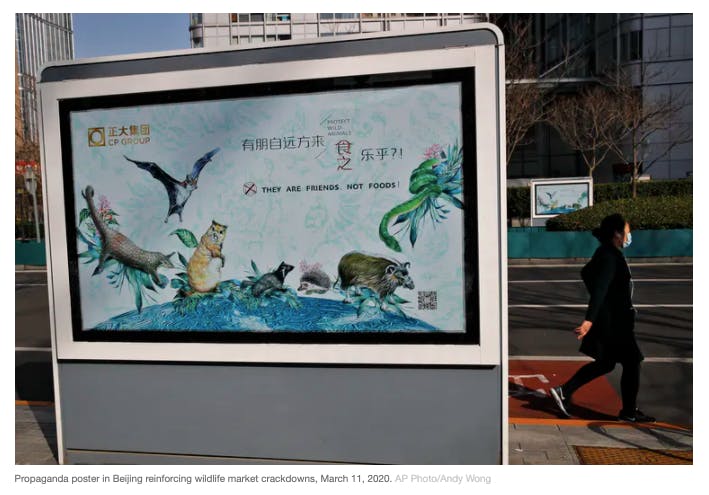

Now repercussions from the Covid-19 pandemic are driving faster, stronger reforms. China has announced a temporary ban on all wildlife trade and a permanent ban on wildlife trade for food. Vietnam’s prime minister has proposed a similar ban, and other neighboring countries are under pressure to follow this lead.

Conservation scientists are hearing rumours that wildlife markets on China’s borders – which often sell endangered species whose sale is banned within China – are collapsing as the spread of coronavirus cuts into tourism and related commerce. Similarly, there are reports that in Africa, trade in pangolin and other wildlife products is shrinking in response to coronavirus fears.

However, I worry that these changes won’t last. The Chinese government has already stated that its initial bans on medicinal wildlife products and wildlife products for non-consumption are temporary and will be relaxed in the future.

This is not sufficient. In my view, terminating the damaging and dangerous trade in wildlife will require concerted global pressure on the governments that allow it, plus internal campaigns to help end the demand that drives such trade. Without cultural change, the likely outcomes will be relaxed bans or an expansion of illegal wildlife trafficking.

Africa has borne the greatest costs from the illegal wildlife trade, which has ravaged its natural resources and fueled insecurity. A pandemic-driven global recession and cessation of tourism will drastically reduce income in wildlife-related industries. Poaching will likely increase, potentially for international trade, but also for local bushmeat markets. And falling tourism revenues will undercut local support for protecting wild animals.

On top of this, if Covid-19 spreads across the continent, Africa could also suffer major losses of human life from a pandemic that could have started in an illegally traded African pangolin.

Like other disasters, the Covid-19 pandemic offers an opportunity to implement solutions that will ultimately benefit humans and the planet. I hope one result is that nations join together to end the costly trade and consumption of wildlife.

is Associate Professor of Fish, Wildlife and Conservation Biology in Colorado State University. This article was originally published on The Conversation.