Tonibung’s compound In Kampung Nampasan, nestled in the Malaysian Borneo state of Sabah, looks like a typical engineering workshop – with metal frames and bars stacked neatly to one side and bags of cement mix piled high. In the corner, there are also solar photovoltaic kits in their unopened boxes.

On the Friday evening of Eco-Business’s visit, the compound is quiet, as staff working in the non-profit organisation have headed home for the weekend. But during working hours, we are told that the same space comes alive with the roar of power cutters, welding torches and other power tools.

Adrian Banie Lasimbang, Tonibung’s founder, has just returned from the highland outskirts of Kota Kinabalu, where he had been overseeing the refurbishment of a microgrid in Terian Village, one of Tonibung’s earliest projects located in the Crocker mountain range.

The village was previously supported by a micro hydropower system, where a mini dam containing a water turbine converted the downhill-flowing river into rotational energy, which was then turned into electricity to power Terian’s 20-odd households.

Lasimbang recently re-fitted the system with solar panels – transforming the grid into a hybrid one. However, the process is more complicated than just installing solar panels and batteries onto village houses.

This is as micro hydro systems generate alternating current (AC), while solar power generates a direct current (DC), which means Tonibung needs to draft a new set of standard operating procedures to help the villagers integrate both electric currents into their homes.

Lasimbang said increasingly funders are asking for the implementation of solar for rural electrification efforts. As a market-based solution, solar power works efficiently as it can be deployed faster and is modular. In neighbouring Sarawak, the government has also embarked on putting in place hybrid solar-hydro systems for its rural electrification programme.

The Terian project is Tonibung’s first hybrid retrofit. Tonibung has also installed solar-hydro grids in other villages that are designed and built from the start as hybrid systems.

There are challenges with using solar installations in rural areas in Malaysia. For example, logistical challenges to safely dispose of or recycle solar waste could arise, said Lasimbang.

“The solar panels have a long lifespan, over 20 to 30 years. Over that period, the batteries will also need to be replaced three to five times. That is a costly endeavour for the villagers,” he said.

“Mining the raw material for the batteries and the panels also has environmental impacts,” he said.

In comparison, given the circumstances, many villages had adopted micro hydro systems, while ensuring that river systems or watersheds are preserved at the same time.

Lasimbang has opted for a middle path: implementing hybrid systems for Tonibung’s new projects and retrofitting older grids to accommodate solar. Hybrid renewable grids using constant river flow provide a baseload of electricity at night and reduces reliance on battery storage for a longer lifespan.

At the same time, the solar panels help offset the loss in electricity when the rivers flow less rapidly, such as during periods of drought.

Tonibung’s workshop at Kampung Nampasan, Sabah. Tonibung is a community-based, Indigenous-led organisation that has been installing micro hydro and solar grids in rural villages. Image: Vincent Tan / Eco-Business

NGO-led electrification efforts

According to the Energy Commission of Sabah, universal access to reliable and affordable energy is a major issue for the majority of the state’s rural inhabitants. The government’s Sabah Energy Roadmap and Master Plan 2040, published in 2023, aims for 100 per cent rural electrification by 2030 – whether through grid connection or microgrids running on hybrid renewables of solar and micro hydro. The commission states that Sabah has currently achieved 96 per cent rural electrification.

To achieve full rural electrification, two programmes have been launched. One is the state government’s Rural Electricity Supply Programme, and another effort is by a collective of local non-governmental organisations, which includes Tonibung.

This collective, which is known as the Sabah Renewable Energy Rural Electrification Roadmap (SabahRE2), has been working towards the state’s goals via a consortium of five grassroots NGOs .

The project began in 2021 with the mapping of villages throughout Sabah with no access to electricity and the NGOs have since surveyed 206 villages. The aim is to install 168 microgrid systems across these villages by 2030.

Cynthia Ong, the chief executive facilitator for civil society group Forever Sabah, which is part of the NGO collective, said SabahRE2 has mapped what they believe to be most, if not all the remaining unelectrified settlements in the state. Work on its “demonstration phase” has begun, she said.

This entails setting up village microgrids in Kinabatangan and Ulu Papar, and another two more in Tongod and Sipitang districts, which SabahRE2 is working to get funding for.

“We are working on financing and delivery mechanisms of the scale-out [for the rural electrification project] , as well as its Safety and Quality Assurance (SQA) Framework,” said Ong.

Ong said the consortium also engaged in co-developing the policy space for mini-grids with renewables, which currently is an unregulated space, hence the need to develop the SQA framework in collaboration with Sabah’s Energy Commission and the wider ecosystem of stakeholders in Sabah’s energy scene.

The aim for this policy engagement, she said, is to have this proposed SQA framework adopted as a standard, which would allow Sabah’s energy ecosystem to grow as more groups advocate for energy equity [where energy supply is affordable for the entire population] and energy sovereignty.

Revitalising communities

Tonibung is also part of the initiative running parallel to the state government’s rural supply programme and has undertaken feasibility studies for 57 communities.

The organisation, whose name is a portmanteau of Indigenous Kadazan words “TObpinai NIngkokoton koBUruon KampuNG”, – meaning Friends of Village Development – has its roots in the Asian Financial Crisis of 1997-1998, when a lack of jobs led local Kadazandusun youths, including Lasimbang, to form Tonibung as a non-profit organisation which would pick up odd jobs and casual work requiring technical skills.

This got Lasimbang involved in sanitation and energy projects. After learning about micro-hydro technology, he and other Tonibung members volunteered for several such projects in Sarawak and later decided to focus on building micro-hydro grids for rural villages in their home state as well.

Lasimbang says that by 2008, Tonibung had begun designing and manufacturing the majority of components for their microgrid projects, which previously had to be imported from neighbouring Indonesia or China.

Adrian Banie Lasimbang, Tonibung founder, (centre, in red) meets with villagers near Kampung Buayan during a regular monthly visit to check on the status of the micro hydro dam, as well as to settle the monthly fee to help with the dam’s upkeep and maintenance. Image: Vincent Tan / Eco-Business

The benefits of electrifying a rural village are almost immediate. For Padan Ukab, an indigenous Lun Bawang farmer from the village of Long Tanid in the Sarawak highlands, food storage and costs have dropped since Tonibung first installed a 28-kilowatt (kW) system in 2019.

“If we brought back meat from Lawas [the nearest town, which is about 150km away from Long Tanid], we either had to finish the meat the same day or cook everything and store it, because we had no freezers or refrigerators,” said Padan.

The costs of using electrical appliances were high, as running a diesel generator at night could cost up to RM10 (US$2.30) per night, using diesel that cost RM3.50 (US$0.80) a litre.

“My fuel for electricity each month came up to about over RM300 (US$70),” Padan said, which is a princely sum for a remote farming community.

The steady, reliable supply of electricity via the micro grid has allowed villagers to purchase more appliances like freezers, fans and lights. Padan’s own household appliances now only cost him RM12 (US$2.80) a month.

“Now the children can study better at night, and for some of us who want to do more work, like handicrafts, there is more light to see as well,” he said.

In Sabah, Irene Kodoyou, a former village head for Kampung Buayan, said the village now has its own workshops doing carpentry and tapioca grinding, business activities which serve as “anchor users” of electricity in the village, according to Lasimbang.

These commercial anchor users can justify the presence of a mini-grid and develop the village’s economy simultaneously, as they can generate enough income to support the maintenance of the grid, said Lasimbang.

“Otherwise, if it’s just the villagers who are paying for the electricity supply, the revenue is not enough to sustain the upkeep of the village grid or (cover the costs) when something needs to be replaced, like the turbine or other grid components,” Lasimbang explained.

A source of pride is Kampung Buayan’s primary school, which also benefits from the improved electricity supply. It previously ranked among the worst in terms of results for rural schools in Sabah.

“Now, results have improved because the stable electricity supply has given more time for children to study, and student intake has also increased,” Kodoyou said.

From a 10kW system in 2022, funded by the United Nations Development Programme, the capacity of the village grid system has expanded with a second 20kW system installed by Tonibung, which supports the growth in size of the village to about 56 households.

Mindset shift

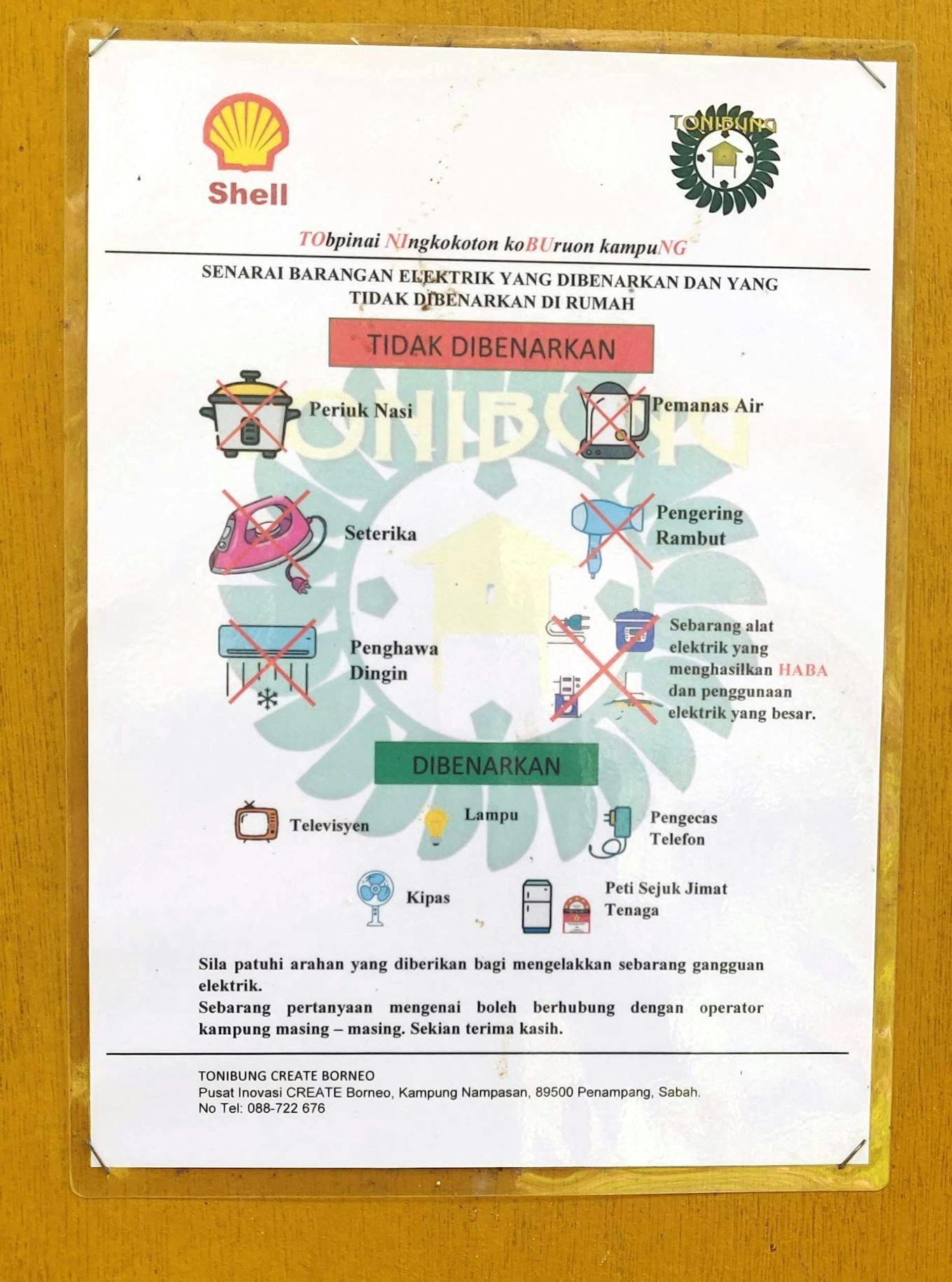

A laminated chart at the powerhouse adjacent to the micro hydro dam that powers Kampung Buayan and a number of other villages in the Crocker Range. The chart explains what appliances can be used in conjunction with the dam’s power output, meaning items which produce heat and use a lot of energy are forbidden. Image: Vincent Tan / Eco-Business

Beyond hardware, Lasimbang said, Tonibung has focused on ensuring that villagers recognise their role as key stakeholders for any micro hydro or hybrid project.

“Besides introducing new concepts like maintenance and systems management to the community, we try to integrate traditional practices like Indigenous concepts of stewardship,” said Lasimbang. “It helps drive home the lessons better.”

Traditional stewardship frameworks such as the “tagal” system – an Indigenous concept later adopted by the state government to conserve its inland fisheries – have also worked well when adapted to preserve the local village’s watershed system

“Construction and setting up the grid only takes up 20 per cent of the time and resources for the project,” said Lasimbang. Another 40 per cent of effort was spent building up trust and obtaining free, prior and informed consent from the community, surveying the landscape and feasibility studies before even striking ground.

During and after the project, the Tonibung also helps the villagers find a self-sustaining use for the micro hydro grid, which means developing local businesses. This could range from opening a welding business, drying produce for sale at town markets, even boat building.

Evan Ng, an analyst with London-based energy consulting firm Baringa, said rural electrification could see faster progress acrossMalaysia. However, the current governance framework in the country poses a challenge.

Central energy planning sits under the Energy Transition and Water Transformation Ministry (PETRA) historically, while rural electrification falls under the Ministry of Rural and Regional Development, said Ng. “Thus, communication and streamlined efforts across these two ministries is needed to accelerate rural electrification in the country.”