In a growing number of developing nations, the push towards clean energy is ultimately a struggle over land use.

Utility-scale solar and wind farms need at least 10 times more land per unit of power produced compared to coal- and gas-fired power plants, according to report by McKinsey.

Addressing land rights is critical for solar developers in Southeast Asia, as the majority of the region’s accessible land is primarily utilised for agriculture.

In archipelagos like the Philippines, however, floating photovoltaic (FPV) systems may surface as a feasible solution in the energy transition – although not without ecological and social risks flagged by civil society organisations.

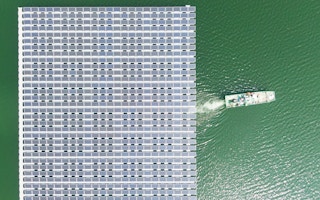

Floating solar – which involves mounting photovoltaic panels on the surface of water bodies such as lakes, reservoirs, industrial ponds and coastal areas – could be a “central pillar in Southeast Asia’s energy future,” said think tank Rystad Energy in a study.

“[The Philippines, Indonesia, and Thailand] have suitable natural conditions – like isolated bodies of water and naturally-occurring ponds – that make FPV viable to install, as well as reservoirs and hydropower dams that are [also] ideal for FPV installations,” Tristan Pheh, an analyst at Rystad Energy, told Eco-Business.

Pheh added that while countries like Malaysia, Vietnam and Myanmar still have plenty of space to develop ground-mounted solar before committing to a large floating solar push, the Philippines has scarce land that can be allotted for solar farms without encroaching on farmland and conservation areas.

Southeast Asia currently only has a total of about 500 megawatts (MW) in operational FPV projects, but that capacity is expected to swell by 300 MW in early 2024 alone. Between 2014 and 2020, the world’s installed FPV capacity has increased more than 250-fold, notes non-profit Forum for the Future’s Responsible Energy Initiative Philippines report.

“Currently, the Philippines does not have much [installed] FPV compared to other Asean countries, but the Philippine government has shown positive support towards accelerating large [floating solar] projects which could lead to a boom in FPV capacity this decade,” Pheh added.

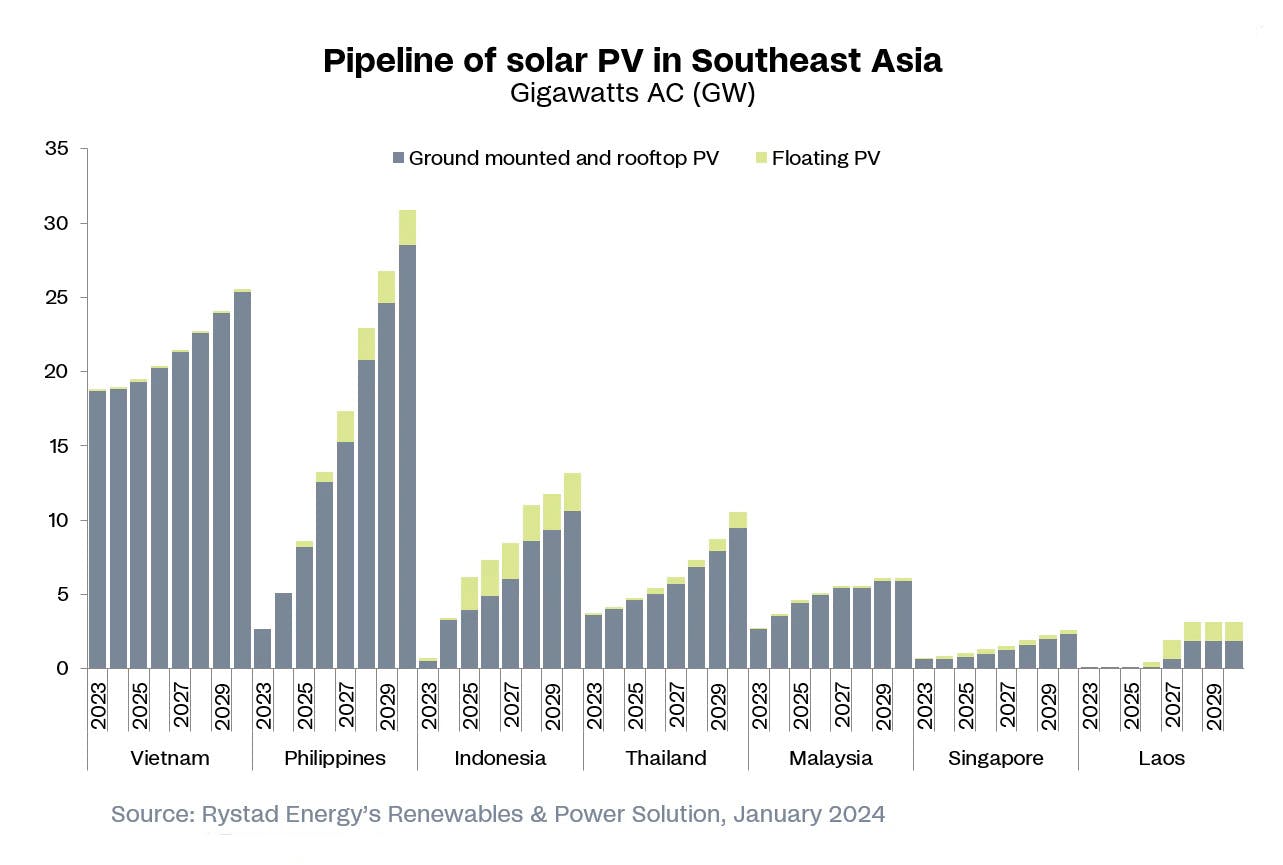

With numerous projects in the pipeline, FPV could make up to 12 per cent of the Philippines’ solar capacity by 2030, according to Rystad Energy.

The Philippines, Indonesia and Thailand are expected to lead Southeast Asia’s push into floating solar. As an archipelago, the Philippines has many large inland lakes that are suitable for FPV, such as Laguna Lake, where there are plans for nearly 3 gigawatts-alternating-current (GWac) of capacity. Chart by Rystad Energy

Transition investments

Fossil fuels still make up a sizeable portion of the Philippines’ energy mix, with coal accounting for 58 per cent of the country’s power generation. Only 22 per cent of the archipelago’s current grid is supplied by renewable energy sources, with solar and wind facilities contributing just 1.4 per cent.

However, with the rollout of the country’s ambitious National Renewable Energy Programme (NREP), the Philippines has quickly risen to have the largest renewable energy development pipeline in Southeast Asia by incentivising foreign direct investment.

In late 2022, the Philippines’ Department of Energy (DOE) also amended the implementing rules and regulations of the Renewable Energy Act to fully open its renewable energy sector to foreign ownership.

The NREP outlines the country’s goal to increase the share of renewables in its energy mix to 35 per cent by 2030 and 50 per cent by 2040. The country is poised to add 17,809 MW of installed solar and 7,856 MW of wind capacity by 2030.

Several FPV projects figure in this pipeline, including Blueleaf Energy and SunAsia Energy Inc’s 1,300 MW floating solar project and a 1,000-plus MW portfolio of five FPV facilities to be established by subsidiaries of ACEN Corp, the energy arm of the Ayala Group – all in Laguna de Bay, the Philippines’ largest freshwater lake, some 30 kilometres south of Metro Manila.

ACEN’s projects have already been granted a “green lane” endorsement by the Philippines’ Board of Investments (BOI). “Green lanes” are granted by the Philippines’ investment agency to expedite the process of obtaining necessary permits for strategic projects.

ACEN’s plants are set to encompass a total of 800 hectares on the surface of Laguna de Bay, while the SunAsia Energy facility is expected to cover 2,000 hectares. The floating facilities are projected to commence construction in 2025 and begin commercial operations by 2026.

“

A key principle upheld by the Responsible Energy Initiative is the importance of a rights-based approach to the scaling of all renewable energy technologies. This includes meaningfully engaging with impacted communities.

Cynthia Morel, principal strategist, Forum for the Future

In a statement, Tetchi Capellan, president and CEO of SunAsia Energy noted that there is “a strong incentive to build on water” as “land use is becoming a big issue for renewables.”

Similarly, Eric Francia, ACEN president and CEO, said in a statement that the company is investing in FPV to “expand [its] clean energy assets while addressing land scarcity.”

In a previous report, the floating solar project lead of SunAsia Energy, noted that the Philippines stands to gain 11 gigawatts in power generation – enough to energise 7.2 million households – from floating solar alone by covering just 5 per cent of the country’s water surface.

Water surface rights

During the launch of the Responsible Energy Initiative Philippines consortium earlier this year, Forum for the Future weighed the sustainability of FPV projects in the Philippines in its Renewable Energy to Responsible Energy: A Call to Action report.

“Floating solar has the advantage of circumventing land acquisition issues associated with traditional solar installations,” Cynthia Morel, Forum for the Future’s principal strategist, told Eco-Business. “However, there is a likelihood of competition for limited resources, as seen in the example of Laguna [de Bay] lake, where scores of livelihoods depend on [the body of water for] fishing and agriculture.”

With a total surface area of 90,000 hectares, some 35 towns dot the shoreline of the Laguna de Bay. The Laguna Lake Development Authority estimates that some 13,000 fishermen rely on the lake for their livelihoods.

In an email correspondence, Maris Cardenas of the Center for Empowerment, Innovation and Training on Renewable Energy cited a 2022 Commission on Audit report that found that private corporations already claim more than 40 per cent of Laguna de Bay’s allowable fishing area – putting the lake’s small-scale fisherfolk at a disadvantage.

“FPVs can pose a threat to water surface rights depending on the total area that will be allowed or allocated for them,” Cardenas told Eco-Business. “A study to determine or set a cap on the maximum area that can be covered by FPVs may be needed. This will take into consideration the number of fishers and the area where fish will [breed].”

Similarly, Morel called for “deliberate steps [to] be taken to uphold fisherfolks’ existing rights,” adding that the “energy transition solves nothing if it leaves society’s most vulnerable communities behind.”

While acknowledging that shading provided by floating solar panels may potentially help mitigate harmful algal blooms and improve water quality, experts at Forum for the Future have flagged a handful of ecological impacts the proliferation of FPV on Laguna de Bay may cause, including disruption to the spawning behaviour of fish, sedimentation, siltation and shoreline soil erosion, among others.

Morel said that a “rights-based approach” was needed to scale renewable technologies, which in the case of FPV will mean engaging fisherfolk on where floating solar platforms are sited to ensure their livelihoods are not affected.

Want more Philippines ESG and sustainability news and views? Subscribe to our Eco-Business Philippines newsletter here.