In India’s ‘Silicon Valley’ tech hub of Bangalore, where gleaming office complexes and apartment blocks have sprouted faster than the plumbing to serve them, only 60 per cent of the water the city needs each day arrives through its water pipes.

Much of the rest is pumped from groundwater wells and delivered to homes and offices by a fleet of private tanker trucks that growl through the city of 12 million’s streets.

But Bangalore’s groundwater is running dry. A government think tank last year predicted the city—like others in India, including New Delhi—could run out of usable groundwater as early as 2020 as aquifers deplete.

By 2030, half of India’s population—now about 1.4 billion people—may lack enough drinking water, the report predicted.

Around the world, fresh water is fast becoming a dangerously scarce resource, driving a surge in fights to secure supplies and fears over rising numbers of deaths in water conflicts.

Growing populations, more farming and economic growth, climate change and a rush of people to cities all are increasing pressure on the world’s limited water supplies, researchers say.

More and more people are dying from contaminated water or conflicts over access to water.

Peter Gleick, co-founder, Pacific Institute

UN data shows 2 billion people—a quarter of the world’s population—now are using water much faster than natural sources, such as groundwater, can be replenished.

In 2015, the United Nations’ 193 members agreed a new set of global development goals, including one to give everyone access to safe and affordable drinking water by 2030.

But in places from Africa to the Middle East, “big rivers are drying out, the population is increasing, demand is piling up and we can’t supply (people) with water and food”, warned General Tom Middendorp, a former Dutch defence chief.

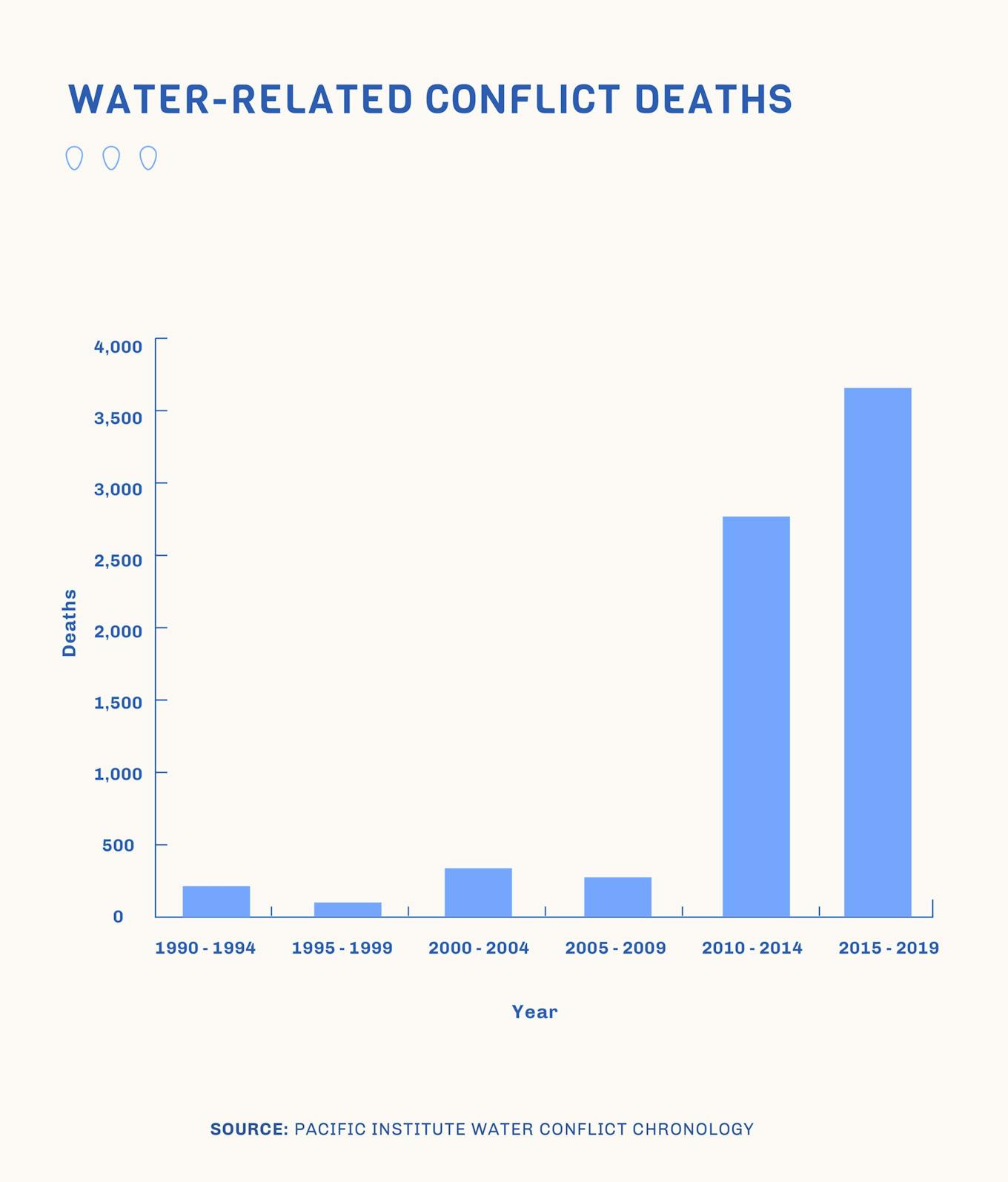

Globally, the number of conflicts related to water scarcity has risen from roughly 16 in the 1990s to about 73 in the past five years, according to a chronology maintained by the Pacific Institute, which tracks freshwater security issues.

In the 1990s, conflicts driven by water scarcity led to about 350 deaths, in places from Yemen to Nigeria, according to the chronology based on news reports and other sources.

But in the last five years, at least 3,000 people—and perhaps more than 10 times that many, if estimates of refugee deaths by Medicins Sans Frontieres are included—have died in clashes related to water in a huge range of countries, it noted.

“We see conflicts over water, unfortunately, almost everywhere around the world now as competition grows over the scarce resource,” said Peter Gleick, co-founder of the California-based Pacific Institute.

“If you look at the number of conflicts over water in the past few decades, it’s going up exponentially.”

Water shortages are likely to lead to a growing death toll in coming decades, as farmers struggle to access enough water to grow crops and families turn to riskier water sources to slake their thirst, researchers say.

So far, “with very rare exceptions, no one dies of literal thirst”, Gleick said. “But more and more people die from contaminated water or conflicts over access to water”.

Besides fuelling conflict, increased water scarcity is also beginning to spark widespread reassessment of how water is captured, managed, shared and used around the world.

In the American West, legal challenges—including by Native American tribes—may reshape old water rights systems that give farmers or cities with “senior” rights as much water as they like, leaving others and natural ecosystems increasingly dry.

The West needs rules “reflective of modern needs and desires, rather than the rules we’ve had for 150 years and have had to stick by”, said Bob Anderson, director of the Native American Law Center at the University of Washington.

Thirsty cities from Singapore to Los Angeles, worried their supplies of water may fall short, are trying innovative ideas to cut water demand and find new sources of the precious liquid.

Singapore, for instance, has thrown a wall across a seafront bay, gradually turning what once was saltwater into a huge new freshwater reservoir for the city-state, which today relies on neighbouring Malaysia for much of its water.

“It is crucial to be water-independent,” said Adam Reutens-Tan, a Singapore resident whose family has slashed its water use, through measures from serving one-pot meals to save on dish-washing to taking five-minute showers.

Los Angeles, which built its growth on water sucked from the distant Owens and Colorado rivers, is looking to capture stormwater and more rain to recharge its own aquifers as climate change and competition threaten its old supplies.

It is also stepping up conservation—including paying residents $3 per square foot to shrink or get rid of water-demanding green lawns.

“As we looked at the future and where we were going to get water reliably, sustainably, we were really looking within,” said Rich Harasick, senior assistant general manager for the city’s Department of Water and Power.

In increasingly parched southern Africa, worsening water shortages in 2017 led South Africa’s Cape Town to launch a public countdown to “Day Zero” when it feared the city’s taps would run dry.

That threat was averted after residents joined a successful drive to slash the city’s water use. Now city officials are restructuring where the city will get its water in the future, including from more wells and desalination plants.

But in rural areas of South Africa, water shortages are also driving villagers to experiment with new drought-hardy crops, and new ways of capturing, sharing and conserving water.

In the village of KwaMusi and others nearby, drought-hardy beans and amaranth—grown in fields snaked through with water-sipping drip irrigation hoses—are showing up on plates once filled mainly with maize porridge, the region’s old staple.

Rainwater harvesting tanks, to catch the runoff from tin roofs, also are being installed, and irrigation pumps purchased, on a continent with one of the world’s lowest irrigation rates.

“These small changes mean the community will have something to eat and sell when water becomes more scarce,” said Brandon Nthianandham, a rural worker for a food security trust helping farmers in the region.

But in many water-short areas, conflict over limited supplies is growing, particularly as dry conditions set in again this year.

This story was published with permission from Thomson Reuters Foundation, the charitable arm of Thomson Reuters, that covers climate change, humanitarian news, women’s and LGBT+ rights, human trafficking and property rights. Visit http://news.trust.org/climate. Read the full special report.