For the first time last year, more dead than living pangolins were shuttled to the Wildlife Healthcare & Research Centre at Mandai, Singapore’s zoo complex, the organisation has confirmed.

Some 23 Sunda pangolins hit by vehicles were ferried to the centre by conservation groups in 2022, according to latest statistics from wildlife rescue centre Acres. Many of them did not survive.

This is a huge jump from official numbers from 2016 to 2021, when an average of three to nine pangolin roadkills were reported a year. Since 2021, the average has crept up to 20 cases a year. 2023 was a record for pangolins hit by vehicles.

So far this year, the number of pangolin casualties has been low. The first roadkill of the year was on Sunday, World Wildlife Day, in a residential area near fragmented forest patches, Eco-Business understands.

Though the absolute number of casualties seem small, Singapore’s National Parks Board (NParks) estimated in 2016 that there are about 100 wild pangolins left. The conservation agency has since stopped publishing population estimates, with NParks reportedly saying that this is because the numbers have been hard to pin down.

The tropical city-state has claimed to be something of a refuge for this critically endangered mammal. While poaching of wild pangolins, the world’s most trafficked mammal, is rampant elsewhere in Southeast Asia, the creature has been relatively safe from the wildlife trade in Singapore.

“

Singapore should deal with the root cause of pangolin endangerment – deforestation – instead of just treating the symptoms.

Jimmy Tan San Tek, nature conservationist

Not entirely, though. In January, an air force regular was caught trying to sell a pregnant pangolin for S$1,400 (US$1,050) on Telegram. The animal, which had been fed fruit and vegetables instead of its natural diet of ants, was recovered in a sting operation by NParks.

In response to Eco-Business’s queries on the latest statistics, NParks said that the main threats to pangolins in Singapore are habitat loss and alteration, as well as road traffic accidents. “This contrasts with the major threats that this species faces regionally, which include poaching and illegal trade,” said NParks’ group director of conservation, Lim Liang Jim.

Nparks also said that the spike in pangolin deaths could be due to “greater public awareness about pangolins and wildlife, and how to go about reporting such cases”.

In Singapore, pangolins have been spared the level of poaching they have suffered elsewhere – one pangolin is poached from the wild every three minutes globally, mainly for its scales for use in traditional medicine, according to conservation group WWF. In Singapore’s case, the biggest threat is urbanisation.

Local conservationist Dr Ho Hua Chew told Eco-Business that a “glaring factor” contributing to the decline of pangolins in Singapore is the loss of remaining secondary forest due to development for housing, industrial estates, transport facilities and military projects.

“Roadkills are inevitable as roads have multiplied and vehicular traffic has become more intense and the green landscape has become more fragmented and concretised,” he said.

Secondary forests and survival

Dr Ho cited areas such as Mandai Lake Road, Kranji Woodland, Lower Seletar, Bukit Gombak, Bukit Mandai and Dover as where development has removed pangolin habitat and food sources. Pangolin roadkill hot spots include Mandai Road, where there has been deforestation to expand Singapore’s zoo complex, and Bukit Timah Expressway, a road that dissects two nature reserves.

Among the most recent patches of secondary forest to go is in Tengah, where a “forest town” is being built. Tengah forest, about half of which has been razed since construction began in 2017, was a key connection point to enable pangolins to move between the Western Catchment forest and the Central Catchment Nature Reserve, observed Dr Ho.

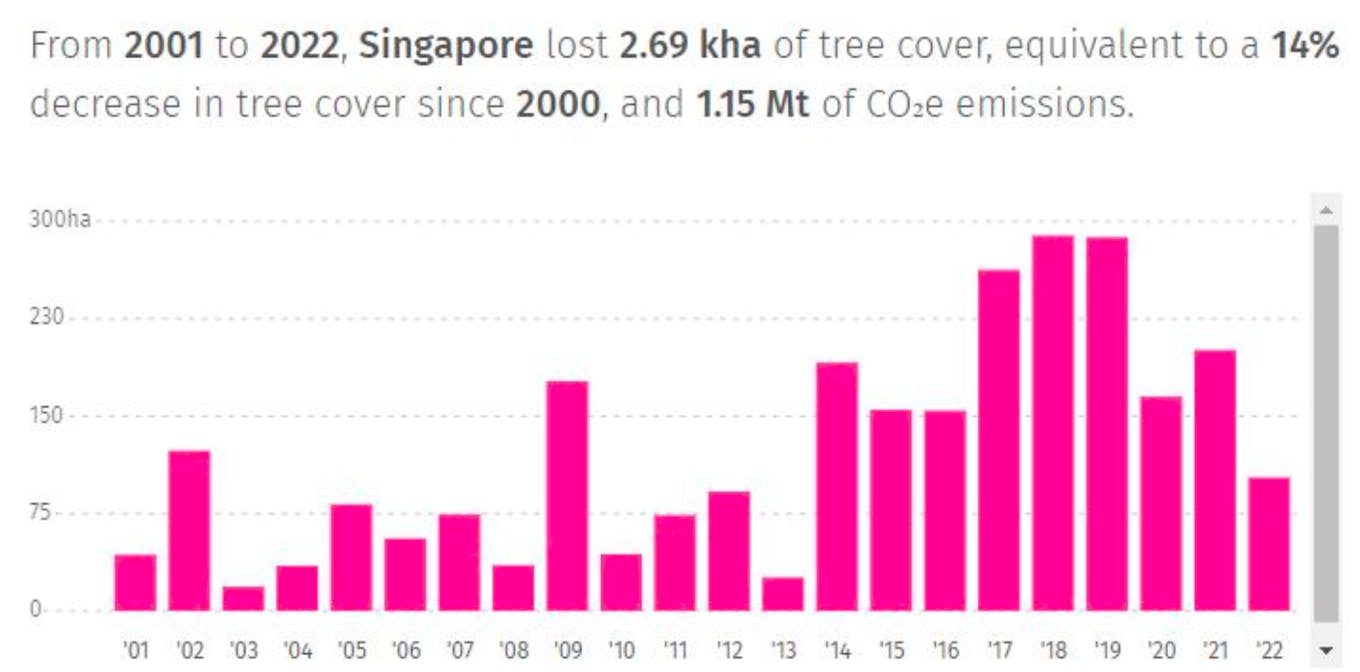

Between 2001 to 2022, Singapore lost 14 per cent of its tree cover. Source: Global Forest Watch

Unlike Singapore’s thriving populations of otters and civets, forest-dependent Sunda pangolins do not fare well in urban environments, and are often rescued by animal welfare groups with injuries from trying to navigate razor-wired fences and other obstacles.

In August 2023, a pangolin was found in the highly urbanised housing estate of Toa Payoh. It was limping. It is likely that the pangolin wandered out of Bukit Brown forest or the remnant of Toa Payoh grave hill forest, due to disturbances caused by the construction of the North-South Corridor, a road that will connect Singapore’s northern region to the city, said Jimmy Tan San Tek, a local conservationist.

NParks has been working to conserve Singapore’s pangolin population by creating a network of nature parks that surround Singapore’s nature reserves to serve as ecological buffer zones. The agency is also trying to improve connectivity for wildlife by setting up nature corridors that act as “ecological stepping stones”.

How Tengah forest has changed since 2017. The district is to be converted into a “forest town”. Image: Jimmy Tan San Tek

However, Tan said most of Singapore’s conservation efforts have focused on nature reserves and buffer parks, not on the island’s secondary forests, which are home to other endangered species, such as the straw-headed bulbul. Secondary forests such as Clementi forest, Bukit Brown forest, and the remaining half of Tengah forest, are in danger of being destroyed or fragmented further, since they are zoned for development, he said.

Secondary forests account for about one-fifth of Singapore’s land area and are vulnerable to development, because they are not protected by law. According to a paper published last year, Singapore could convert 7,331 hectares of secondary forest – an area 1.2 times larger than that of all the parks and nature reserves combined – over the next 10 to 15 years, according to the country’s urban development plan.

Tan said that in some areas the nature corridors are too thin to enable pangolins to move comfortably around the island. For instance, the 100 metre-wide nature corridor at Tengah is “grossly insufficient” to ensure that pangolins can burrow safely, since they will find themselves in uncomfortably close promixity to the housing development, Tan has argued.

Further population declines can be expected if they continue to lose forest habitats and ecological connectivity, and experience inbreeding as populations become increasingly isolated, Tan said.

Dr Ho noted that while efforts to create wildlife corridors in Singapore are laudable, such efforts are pointless if the remaining patches of secondary forest are drastically curtailed or wiped out. “There is an urgent need to be consistent in our conservation work – for the sake of the long-term survival of not only the Sunda Pangolin but all of our remaining wildlife,” he said.

“The need to preserve more of the remaining forests outside the nature reserves should be the overarching focus of our conservation efforts,” Ho said.

Singapore, which brands itself as a “city in nature”, committed to end deforestation by 2030 when it signed a pledge with 130 other countries at the COP26 climate talks in 2021.

“By the time Singapore heeds the no-deforestation by 2030 agreement, there may not be much forest left for the pangolins to continue surviving in the wild,” Tan said.

Singapore should prioritise recycling previously developed lands instead of sacrificing the forests for housing and other developments, he suggested.