One of Indonesia’s few remaining expanses of pristine rainforest is at imminent risk of destruction by Korean-Indonesian conglomerate Korindo, a new report by an international group of environmental campaigners has found.

Titled ‘Burning Paradise‘, the report released on Thursday said that Korindo — a Korean-controlled, Jakarta-headquartered company — is burning land in Indonesia’s remote Papua province to make way for oil palm plantations, and destroying ecologically-valuable land in the process.

Through field investigations in Papua over the past few years, the groups behind the report — Dutch consultancy Aidenvironment, new American environmental group Mighty, the Korea Federation for Environmental Movements, and Indonesian non-government organisations SKP-KAMe Merauke and Pusaka — found that Korindo was also violating the rights of communities in its concessions.

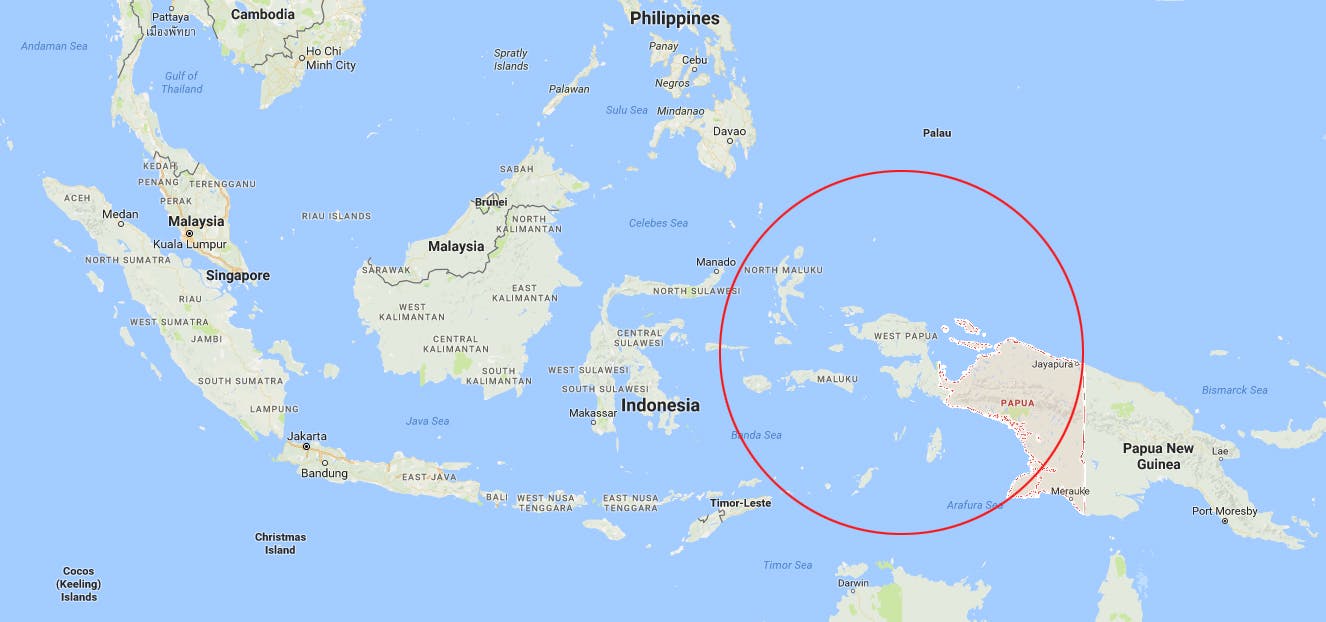

Korindo was set up in 1969 and has some 30 companies and 20,000 employees spanning across palm oil production, newsprint paper manufacturing, as well as industries such as wind towers, financing, and real estate. It developed its first palm oil plantation in Indonesia in 1998, and now has eight concession areas in Papua and North Maluku provinces, totalling 160,000 hectares.

It plans to increase its plantation area in Indonesia to 200,000 hectares by 2020, according to a statement on its website.

Korindo has 160,000 hectares of oil palm concessions in Indonesia’s far-flung Papua and North Maluku provinces. Image: Google Maps

Mighty’s campaign director Deborah Lapidus said in a statement that “the extent of Korindo’s systematic clearing and burning of Indonesia’s pristine rainforest is downright tragic”.

“But what’s shocking is that the world’s major buyers of palm oil kept Korindo in their supply chains for more than two years after adoption of their No Deforestation policies,” she added.

The company’s clients, until recently, included palm oil giants Wilmar, Musim Mas, ADM, and IOI. Many of these firms have in recent years adopted strict commitments across their entire supply chain against deforestation, peatland development, and community exploitation.

These companies, which grow and process palm oil, sell the commodity on to consumer goods manufacturers like L’Oreal, Biersdorf, and General Mills, meaning that tainted palm oil could be in widely-used products such as cosmetics and food items.

However, these companies stopped buying palm oil from Korindo when the NGOs behind the report shared evidence of the conglomerate’s destructive practices with them earlier this year.

But the companies should have caught Korindo’s deforestation and illegal burning sooner, said Lapidus.

The company had been under scrutiny by green groups as early as 2013, when activist groups such as Greenpeace had published imagery of rampant burning on Korindo-owned concessions. Conflicts with local communities in some of its concessions were reported even earlier, in 2007.

Lapidus added: “It’s hard to miss 34,000 hectares of deforestation in the middle of a pristine rainforest”.

A new palm oil frontier

Papua is home to Indonesia’s largest area of untouched primary rainforest and half of the country’s biodiversity. While many natural ecosystems in Sumatra and Kalimantan have been lost to the booming agribusiness sector, Papua at the end of 2012 was still covered by some 35.2 million hectares of primary forest.

A tree kangaroo in the forests of Papua, Indonesia. The endangered marsupial’s habitat is threatened by agribusiness expansion. Image: Bustar Maitar, Mighty

But the relatively inaccessible province has in recent years caught the eye of oil palm firms because large tracts of land have become increasingly difficult to find in Sumatra and Kalimantan. At the same time, government oversight of companies operating in the latter areas has also increased in a bid to slow deforestation and prevent burning.

As a result, the number of palm oil companies operating in Papua increased from five in 2005 to 21 operational plantations in 2014, with another 20 awaiting permits. Korindo, which has had a presence in Papua since 1993 through its other forestry businesses, is currently the biggest palm oil company in the province.

According to the report, the company has cleared about 50,000 hectares of forest since 1998 — an area the size of Seoul, South Korea — and about 30,000 hectares of this land were converted to oil palm plantations in the last three years alone. Since 2013, the company has cut down some 11,000 hectares of primary rainforest for oil palm plantations, the report added.

Korindo’s operations have largely been conducted away from the scrutiny of investors or community observers because it is not a public company, the reported noted. This exempts it from the reporting and transparency requirements mandated by stock exchanges.

The fact that Papua is so remote, and therefore more difficult to access than Sumatra and Kalimantan — where media and civil society groups have paid a lot of attention to corporate deforestation — also allowed Korindo to get away with destroying forests for oil palm plantations with near zero accountability, said the report.

“

Since 1998, Korindo has cleared about 50,000 hectares of forest — an area the size of Seoul, South Korea.

Documented violations

While the company’s website displays a statement that it is committed to developing plantations in an environmentally and socially responsible manner, it does not have a formal sustainability policy. Field investigations also revealed extensive environmental and community rights violations that contradict the company’s claims.

Not only is Korindo cutting down thousands of hectares of primary rainforest to make way for plantations, and likely using the timber in its plywood mills, investigators claim that it is also setting fire to the remaining biomass to break it down and clear the land for plantations. This practice is banned by Indonesian law.

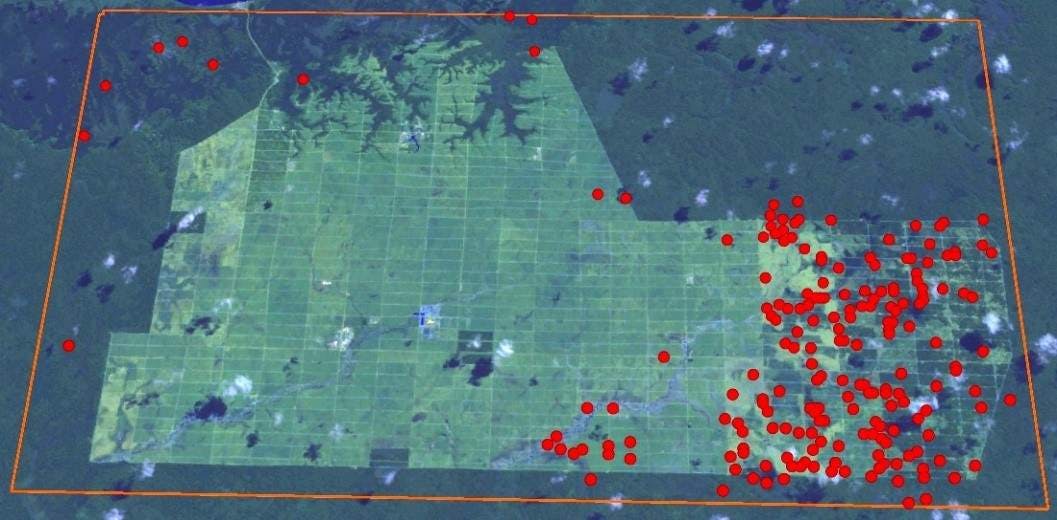

Activists counted some 894 hotspots within the concession boundaries of Korindo’s subsidiary companies between 2013 and 2014, and found that these hotspots occurred between the time Korindo cleared the forest and started planting oil palm. This strongly indicates that Korindo used fire to clear biomass to prepare the land for planting oil palm.

Thanks to these burning practices, the report notes that Korindo was a contributor to Indonesia’s haze disaster in 2015, accounting for almost 1 per cent of all fires. The haze in 2015 was particularly bad, killing 20 people in Indonesia and causing 500,000 respiratory illnesses in the archipelago nation. It also affected neighbouring countries Singapore and Malaysia and drove pollutant indexes in Indonesia to record highs.

When questioned by a Korean news outlet in May this year, Korindo denied using fire to clear land, but offered no evidence to counter the investigator’s claims.

Satellite imagery showing fire hotspots on Korindo-owned plantations in Papua. Image: Mighty

All Korindo plantations are also located in areas that are subject to the customary rights of indigenous people, the report said, adding that the company does not always respect these rights before converting the land to plantations.

For example, Korindo has since 2005 held concessions for about 19,000 hectares of land in Papua through its subsidiary, PT Tunas Sawa Erma. Local tribe clans own most of this land and rejected Korindo’s plantation proposals, but the firm last year proceeded to clear land in these areas anyway.

A man from a local tribe stands on the edge of Korindo’s PT. Tunas Sawa Erma plantation. Local people have objected to Korindo’s plantations on their land, but the company has continued to move forward with clearing the land. Image: Mighty

It is also operating plantations on community lands against their wishes in South Halmahera in North Maluku, which is undermining indigenous people’s food and water security, as well as their access to income from forest resources.

In 2012, villagers protested against Korindo’s expansion in South Halmahera via its subsidiary PT Gelora Mandiri Membangun (PT GMM). Many were arrested, a move that drew sharp criticism from Indonesia’s human rights commission.

Earlier this year, conflict flared up again when the company allegedly evicted people from their land and threatened those who refused to leave. This prompted Indonesian environmental group Walhi to announce that it was suing Korindo for failing to observe legal processes, lacking proper permits, and ignoring customary rights. Walhi’s North Maluku branch is currently pursuing the lawsuit.

YL Franky, director of Pusaka, said that “indigenous peoples’ rights have been abused systematically by Korindo, which has destroyed the forests that are their source of livelihood”.

He added: “This must stop and the government must protect the indigenous peoples’ rights and the forests they rely on.”

“

Indigenous peoples’ rights have been abused systematically by Korindo, which has destroyed the forests that are their source of livelihood.

YL Franky, director, Pusaka

Urgent action needed

There are about 75,000 hectares of pristine forests remaining in Korindo’s oil palm concessions — and more in its timber allotments — and the company urgently needs to protect these valuable ecosystems, said the report’s authors.

They called on the conglomerate to immediately enforce a moratorium on all new forest clearing and burning, and to adopt a policy that protects high carbon stock landscapes across all forest commodities such as palm oil, timber, and pulpwood.

Campaigners added that the company must stop its operations in South Halmahera, return customary lands and resolve social conflicts. They said Korindo must also fix the ecosystems it has damaged and finance the restoration of an area at least equivalent to the land it has destroyed.

Mighty’s Lapidus told Eco-Business that the company refused to meet with campaigners after they sent the report’s findings across in June this year. Korindo also did not respond to queries from Eco-Business.

But when the group sent Korindo’s clients like Wilmar and Musim Mas the findings, both companies conveyed them to Korindo and decided, based on Korindo’s response, to terminate their commercial relationships with them, shared Lapidus.

While decisions by these individual firms are a step in the right direction, “the example of Korindo shows that company-by-company efforts to stop deforestation and human rights abuse are inadequate, and that an industry-wide ban on deforestation is needed immediately,” she added.

There are, however, some signs that Korindo may be bowing to industry pressure to become more sustainable. Shortly after Musim Mas and Wilmar’s exit, PT Tunas Sawa Erma in early August announced a moratorium on forest clearing while it develops a no-deforestation policy.

But this is only a small fraction of its extensive palm oil and timber operations, which are rife with destructive and unethical practices, said activists.

Lapidus noted: “If Korindo continues down this path, it will be at high risk of losing additional customers, losing investors, facing extreme reputational damage, and being held legally accountable for its actions.”

“Or, Korindo could choose to join the revolution in responsible agriculture and turn over a new leaf,” she said.