Each year, Australian households throw out some A$8 billion worth of edible food, with those aged 18 to 24 reported as the biggest wasters.

However, this household figure is likely far outweighed by the value of food waste generated by commercial retailers. In truth, our youth are but one contributor to what could be deemed a massive market failure.

But some people are looking for different ways to approach food and waste. Over three months I interviewed 21 young environmentalists from Melbourne, exploring how and why they began “dumpster diving”: searching waste bins for food.

While there are many reasons why someone might choose—or be forced by economic circumstances—to investigate trash, the young people I spoke to cited a range of motivations: to reduce waste; to create a sense of community; and because they did not want to support unsustainable food markets.

Understanding dumpster diving

Food waste is estimated to cost the Australian economy A$20 billion a year (this includes commercial and industrial sector waste, as well as waste disposal charges).

The Australian government is developing legislation with the aim of halving food wastage by 50 per cent. Effective solutions could result in tremendous savings and considerable environmental benefit.

While dumpster diving is obviously not a wholesale solution to the problem of food waste, young consumers’ changing attitudes are an important part of our national conversation.

My findings show that Melbourne’s young environmentalists regularly visit dumpsters at vegetable markets, supermarkets and bakeries.

My interviewees were motivated to dumpster dive by a range of factors besides the obvious gain of free food and goods. Framing the deed as economic necessity fails to capture a variety of incentives.

It’s worth noting that the limited demographic I studied means these results cannot be associated with those who dumpster-dive out of genuine need. Rather, those I interviewed wanted to reduce food waste and avoid supporting the “mainstream” food economy. One young environmentalist told me: “I never in my childhood and afterwards had a shortage of food in my life. I think the reason that I started [dumpster diving] and one of the main reasons that I continue it is because I think it’s environmentally a good thing to do […] I am not buying things. I am not contributing to unsustainable food production.”

Several participants said they refused to buy from companies with unacceptable environmental credentials. For them, dumpster diving is not an occasional activity but a planned and ongoing way of life. They attempt to create an alternative “free” food economy based on minimising waste and sharing resources.

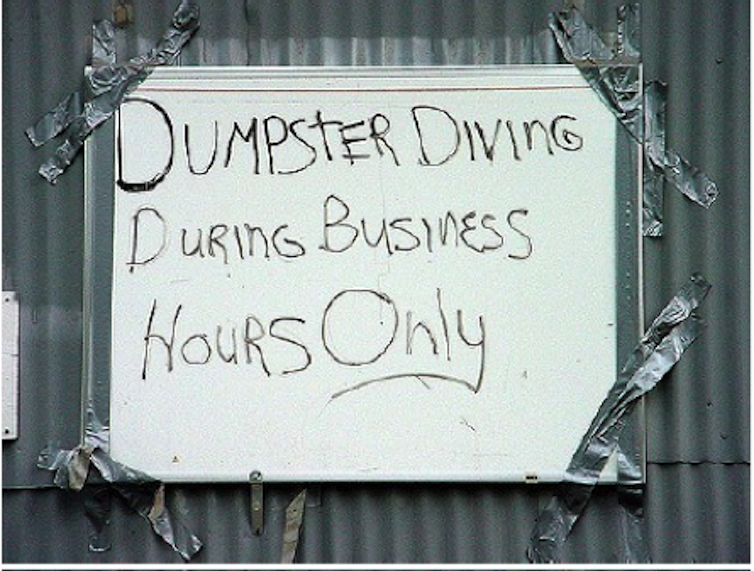

However, members of the group are aware of opposition to the practice. Several had experienced confrontations with retail staff, security guards and members of the public. One interviewee said: “I think they [supermarket authorities] worry about losing business [as] people get food from their bins, not from the supermarket; it’s a part of their worry as well. They ask me to leave. I ask, ‘Why?’ It’s ridiculous. Why can’t they let me have this food that will probably end up in landfill?”

Feel-good and fun

Dumpster divers are also motivated by the emotional bonds they form as a group. They’re part of a broader subculture of “alternative” consumers, who commonly share food; they describe themselves as “a community of free food people”.

Several expressed a “feel good” and “fun” dimension to the activity. Acquiring unpredictable “finds” created a sense of novelty and surprise, and a feeling that the rewards were “worked for”. They mirror more traditional shopping habits like “treasure-hunting”, or the thrill of finding a bargain.

Retailers’ perspective

From a retailer’s perspective, dumpster diving presents a different face. Although one interviewee accused retailers of protecting their profits, there’s also the risk of a dumpster diver being injured, or getting sick from unsafe food.

While some companies actively support or are empathetic towards dumpster divers, others call for the prosecution of divers whom they believe to be stealing. Diving is illegal in many developed countries such as Germany and New Zealand (although prosecutions are rare).

The purpose of dumpster diving is to highlight and provide an alternative to the food waste embedded in everyday business models.

Everybody involved in the food chain has a role to play in reducing food waste. Retailers can work to optimise their supply chain, reduce the amount of produce on display or accept less-than-perfect produce from farmers. Products approaching expiring should be heavily discounted, or donated to charities (although food banks aren’t a panacea).

We as consumers should also be willing to adjust our expectations of perfect produce, something explored in the ABC programme War on Waste and campaigns like the United States’ Ugly Fruit and Veg.

More fundamentally, we need to change our attitude to food. Thinking about why and how we create waste and exploring different perspectives – like dumpster diving – are all part of this process.

![]() Ultimately, the purpose of dumpster diving is to highlight and provide an alternative to the food waste embedded in everyday business models. At the end of the day, the way forward is for each of us to consider and reflect on our own habits of consumption.

Ultimately, the purpose of dumpster diving is to highlight and provide an alternative to the food waste embedded in everyday business models. At the end of the day, the way forward is for each of us to consider and reflect on our own habits of consumption.

Chamila Perera is Lecturer at Swinburne University of Technology. This article was originally published on The Conversation.