Efforts to agree on an accord to stem the proliferation of plastics stalled on Friday, leaving almost three years of negotiations in limbo.

Delegates walked away from the United Nations meeting in Geneva, Switzerland without a pact, after two weeks of fraught negotiations over how to address the threat that plastic pollution poses to human health, wildlife and ecosystems.

“The meeting was adjourned without any clarity of the course ahead. We don’t have any clue about when and where this would be, and who will finance such a meeting. We are in a limbo,” said Arpita Bhagat, plastics policy officer for the Asia-Pacific region at non-profit Global Alliance for Incinerator Alternatives, who was observing the talks on the ground.

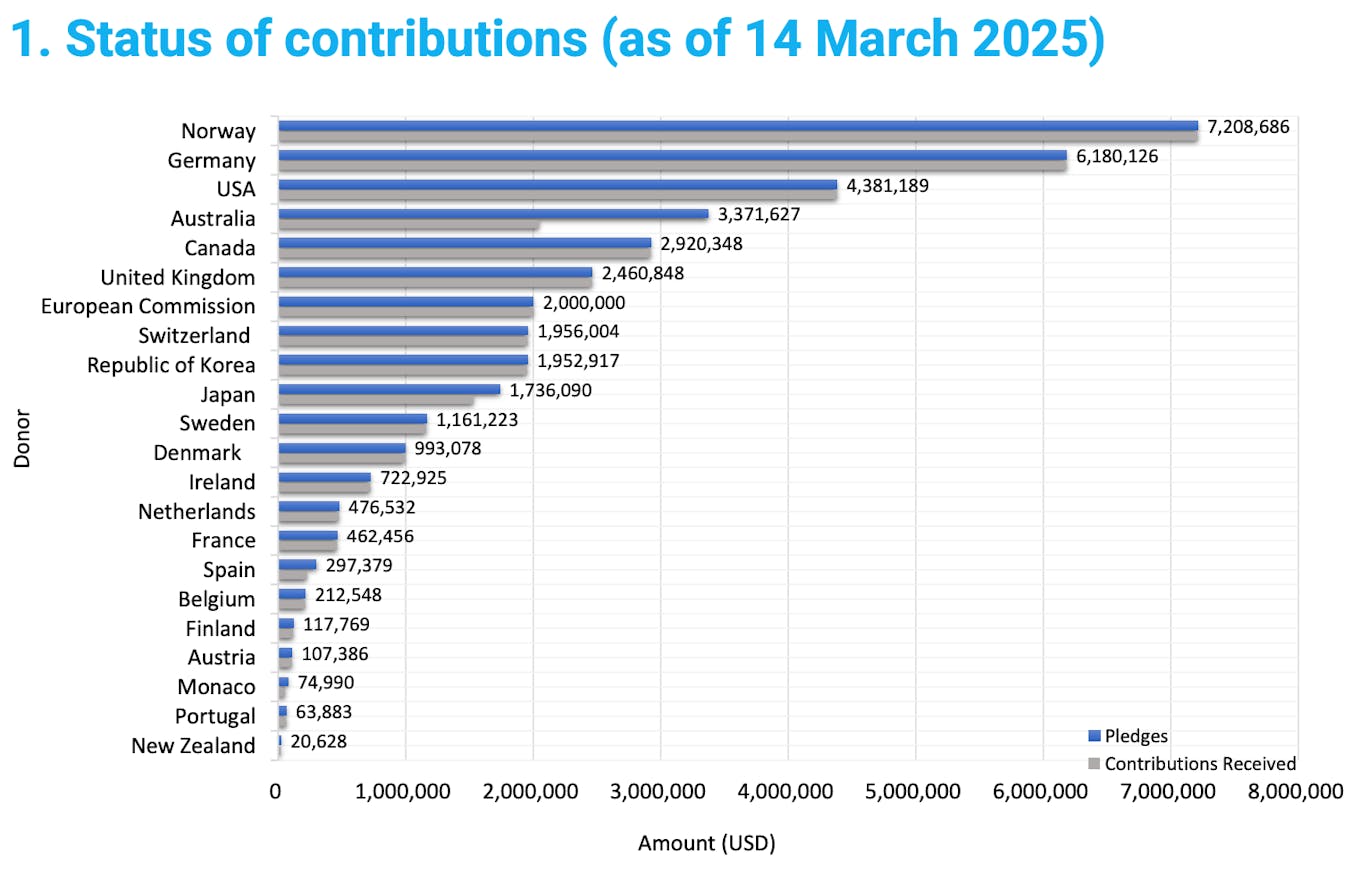

Contributions to the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) to develop a legally binding instrument on plastic pollution, including in the marine environment, have reached almost US$40 million since the first session took place in Punta del Este, Uruguay in 2022.

The United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP) raises funds from participating countries to pay for treaty sessions which include expenses for delegations, logistics, and support staff.

“

There is only appetite for another session if it can be shown that the dynamics and approach will be different.

Christina Dixon, oceans campaign lead, Environmental Investigation Agency

Bhagat noted the possibility for the chair of the negotiating committee to organise smaller gatherings among participating countries. However, she said that civil society feared that they may be excluded from such meetings, where a lack of resources could be cited as a reason for not inviting observers.

Even if a country steps up to host, the talks will be stalled once more if the process does not change, warned Christina Dixon, oceans campaign lead of London-based non-profit Environmental Investigation Agency (EIA).

“Everyone was completely exhausted [after the conference] and there is only appetite for another session if it can be shown that the dynamics and approach will be different,” said Dixon.

After working through the night, heads of delegation arrive for closing plenary on 15 August. Image: Kiara Worth/ IISD-ENB

She noted that the final round of negotiations exposed “deep geopolitical divides and a troubling resistance to confronting the real drivers of plastic pollution.”

Such a divide has hung over six rounds of negotiations in the past three years since the talks began.

Delegates have struggled to mediate the split between the high ambition coalition, composed of countries that favoured a treaty that would cap the amount of plastic produced and set limits on certain toxic chemicals, and a smaller bloc, known as the like-minded group. They are made up of oil-producing countries including Saudi Arabia, Iran, Egypt, and Kuwait that wanted to keep the agreement’s focus on plastic waste collection and better recycling.

Dixon said: “No deal is better than a toothless treaty that locks us into further inaction, but without urgent course-correction, efforts to secure a plastics treaty risk becoming a shield for polluters, not a solution to the plastics crisis.”

High-ambition countries are the biggest financiers

Countries pushing for mandatory, global caps on plastic production have been the biggest funders of the treaty talks since 2022, based on UNEP data.

Norway, co-chair of the high ambition coalition, has contributed the bulk of financing at more than US$7 million, followed by Germany.

The United States, the third largest funder, was previously a supporter of plastic production limits, but pivoted to align with the like-minded group, upon a directive from President Donald Trump.

Pledges and contributions received for the Intergovernmental Negotiating Committee (INC) talks since 2022. Image: UNEP

Despite the high ambition coalition being the majority, they are held hostage by the veto powers in consensus decision-making which allows the like-minded group to prevent progress, said EIA’s Dixon.

“While ambitious countries consistently held the line and rejected the prospect of a weak treaty, the failure to reach agreement is a blow to multilateralism, with devastating long-term consequences for our environment, health and future generations,” she said.

High ambition and “middle countries” finding common ground

With China, the world’s largest plastic producer, and Indonesia, one of the biggest plastic polluters, seen to be ramping up efforts for a more ambitious text for a treaty, “middle countries” like them and high ambition members may be finding common ground, said Dixon.

“Middle countries” refer to those that have not officially aligned themselves to either bloc.

Diyin Lu, delegate of China, speaks at a plenary on 7 August. Image: Kiara Worth/ IISD-ENB

She noted how Indonesia provided a submission on production reduction which signalled a “potential softening of position” on upstream measures aimed at curbing the processing of fossi fuel-based feedstock.

Although the Southeast Asian nation has ambitious national targets to reduce marine plastic leakage and improve waste management, the official national position is focused more on downstream interventions, such as waste collection and recycling, rather than legal obligations to cut global plastic production at its source.

China’s closing plenary statement also telegraphed a “more constructive and open tone on key issues like the debate on the plastics life cycle”, she added.

In a statement, Greenpeace China said plastic pollution must be addressed “through the entire chain from production to waste management.”

However, this positive tone has yet to be translated into its negotiating position, which could help to break the two-year deadlock in negotiations and start a new page of global governance aimed at ending plastic pollution, read the statement.

“It will be critical moving forward to focus engagement on finding a path forward with countries who are engaging in good faith negotiations. This will mean some level of compromise, but it does mean not giving up entirely on ambition,” said Dixon. “The fact that the like-minded group rejected the second chair’s text, which was still a very low ambition treaty, proves that they simply want nothing at all.”

At the close of the sessions, nations discussed changing the decision-making process from strict consensus to allowing decisions by voting. Currently, the treaty requires consensus for substantive decisions, with voting by a two-thirds majority only as a last resort when consensus efforts have been exhausted. However, the consensus-based process has led to stalemates and slow progress, with a minority of countries blocking agreements.