As oil becomes more expensive to produce and its demand falls in line with a future where global temperature increase is limited to 1.5 degrees Celsius, national oil companies are at risk of not being able to deliver returns on public funds.

In Southeast Asia, this risk is highest for Malaysia’s state-owned oil firm Petronas and its counterpart in Indonesia, Pertamina, according to the Natural Resources Governance Institute (NRGI), an independent non-profit organisation.

The two companies are among the top four national oil companies in the world that stand out for having “high-cost oil that is at real risk of not generating public returns to citizens,” said Patrick Heller, chief programme officer at NRGI. The other two companies are Colombia’s Ecopetrol and Nigeria’s National Petroleum Corporation.

The findings are drawn from an NGRI report published last week, titled Riskier Bets, Smaller Pockets and which scrutinised the public spending of national oil companies amid the energy transition. The report analysed 58 national oil companies around the world, drawing on data from NRGI’s database and Rystad Energy.

Of a planned US$1.8 trillion investments into new upstream developments, almost half could become unprofitable by 2050, if global oil demand falls in line with national net-zero pledges, NGRI’s report said.

Despite the high fiscal risks, Petronas and Pertamina have increased their investment pipelines since 2021, NRGI’s report showed, with Petronas posting the fifth largest increase in investment pipelines globally within the past two years. It was closely followed by Pertamina and Thailand’s state-owned PTT.

Their combined investments, and those of other NOCs in Asia Pacific such as Thailand’s PTT and China’s CNOOC, CNPC and Sinopec, made the region the largest area of investment growth.

“Those bets are getting riskier for the climate and riskier for their citizens,” said Heller at a virtual press conference on Thursday which focused on the role that national oil companies play in the climate crisis.

NGRI’s findings were in line with other studies, including another recent report by Carbon Tracker. Titled PetroStates of Decline, the report finds that oil-producing countries which depend on petroleum-related revenue face substantial fiscal risks from the energy transition, as falling oil and gas demand is set to put downward pressure on commodity prices. Out of 40 analysed, 28 would lose more than half of expected revenue even if the energy transition was just moderately paced.

“Although these national oil companies often have lower production costs than their listed peers and may stay profitable for longer, they are particularly vulnerable to falling oil prices as demand moves away from oil and gas,” said Guy Prince, senior analyst on Carbon Tracker’s oil and gas mining team who co-authored the report.

African countries were found to be particularly at risk of fiscal impact but Malaysia is also on Carbon Tracker’s list of vulnerable petrostates, which are countries that rely heavily on oil and gas revenue for their national budgets. In 2022, petroleum-related revenue made up 28 per cent of Malaysia’s federal budget, compared to less than 10 per cent for Indonesia. The Malaysian government expects this percentage to decline to 23 per cent this year.

“We noticed a general rise in state indebtedness among petrostates and lower credit worthiness, which will impact their borrowing costs and exacerbate the issues faced by the declines in oil and gas revenues,” said Prince.

Using data from Rystad Energy, the International Monetary Fund and CTI analysis, Carbon Tracker mapped the vulnerability of government revenues in petrostates during a moderately paced energy transition. Image: Carbon Tracker

Unprepared for a transition

NGRI also analysed the public statements of national oil companies globally to gauge their readiness for a transition towards reduced oil and gas demand in the long term.

“Out of the 21 companies we looked at, only nine acknowledged that the energy transition requires them to change their core business strategies,” said Heller. Only five companies said they had a plan, and even then, those plans were short on details, he said.

Carbon Tracker’s Prince echoed this, saying that despite some countries’ enormous fiscal dependence on oil and gas revenue, many national oil companies have not been subjected to the same pressures to transition away from their core businesses as their peers.

The World Benchmarking Alliance’s oil and gas benchmark published in June 2023 confirmed these observations. It found that the level of transition plan readiness for national oil companies is three times lower than their international counterparts.

“This is not to say that international oil companies are an example of good practice, because they are clearly not, but in many cases, [due to] a lack of disclosure, transparency and production plans, we see that national oil companies transitions plans are lower,” said Joachim Roth, climate policy lead at the World Benchmarking Alliance.

“What we find is that no national oil company is effectively planning for a just transition,” he said at the same press conference. Citing Petronas, Roth said that despite some state-owned oil firms positioning themselves as having energy transition strategies, further checks revealed that few had an overall coherent strategy that assessed social impacts.

Dugongs against Adnoc

An aerial view of Bu Tinah island, located off the western coastline of Abu Dhabi and which sits within the Marawah Marine Biosphere Reserve. Image: Aenaon/ Wikimedia Commons

National oil companies feature heavily at this year’s COP28 in Dubai, as the president of the conference is also the chief executive of the United Arab Emirates’ state-backed oil producer Adnoc. The strong presence of oil and gas executives and reports that oil and gas deals are being tabled at the climate change conference has fuelled controversy surrounding the event.

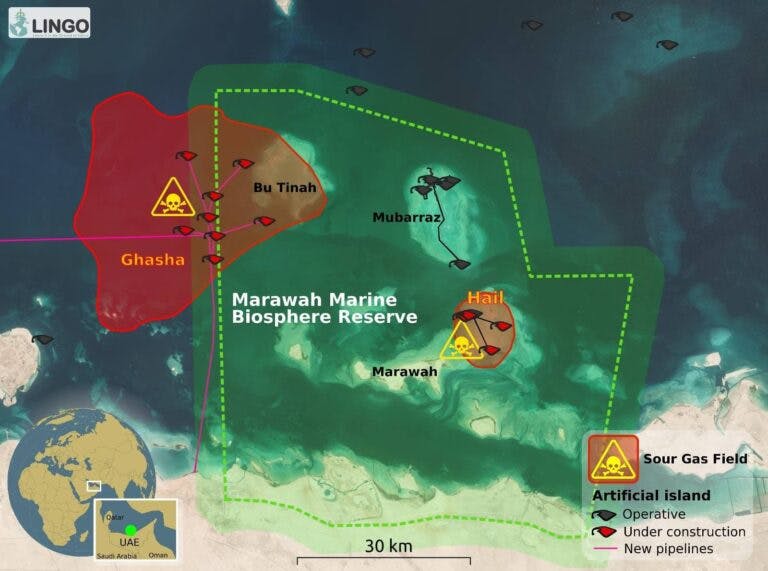

Now, environmental groups are calling attention to Adnoc’s plans to drill for oil in the protected Marawah Marine Biosphere Reserve, recognised by UNESCO and home to the world’s second largest population of dugongs. The UAE has designated the area as a marine protected area by law.

On its website for the Hail and Ghasha development, Adnoc acknowledges that the fields are located within the Marawah Marine Biosphere Reserve, which is home to biodiverse coastal ecosystems and a significant dugong population. Part of the national oil company’s plan to minimise its marine footprint is to build artificial islands to “provide habitats to marine life by eliminating the need to dredge over 100 locations for wells”. Adnoc also said that it has worked closely with the local environmental agency to conduct an environmental impact assessment, the findings of which inform its biodiversity monitoring programme.

However, there are significant risks surrounding the project. The fuel being pumped from the Marawah site is ultra-sour gas, which is more corrosive than other forms of natural gas due to its higher concentration of hydrogen sulphide. Historically, ultra-sour gas has not been mined due to the significant technical challenges faced in transporting it.

“To us, it is a sign that the end of an easy, accessible resource has been reached. So now they are going for more challenging places…pushing into ever-more sensitive environments,” said Kjell Kühne, director of the Leave it in the Ground Initiative. The initiative, which campaigns for the world to transition completely to renewable energy, is also behind the Dugongs against Fossil Fuels campaign.

Kühne adds that Adnoc has greenwashed the project, having stated that it aims to have it operate as a net-zero emissions project but count only Scope 1 emissions, which are generated from the company’s operations, and exclude Scope 2 and 3 emissions, which are indirect emissions and those generated from the use of fossil fuels produced.

“I would call that Scope 3 denial,” said Kühne.

The Leave it in the Ground Initiative calls for Adnoc and the companies involved in the Ghasha and Hail devleopment to pause the project and withdraw their collaboration, as well as the UAE to cancel plans for drilling within the biosphere reserve.

A map showing the areas in which the UAE’s national oil company Adnoc is mining for gas within the Marawah Marine Biosphere Reseve. The reserve is home to the world’s second-largest population of dugongs. Image: LINGO