The palm oil industry has become increasingly reliant on satellite as well as drone technology and visuals for monitoring purposes. Like the concept of photography using cameras, satellite imagery are snapshots taken from high elevations.

Satellites and its imagery outputs are progressively becoming more sensitive and detailed with the added use of radar and laser technology to complement it. Industry players, including Wilmar, have adopted the use of satellite technology for our monitoring efforts.

Satellites for monitoring

While satellite images and technology have improved by leaps and bounds, it is important to understand that it is not just about the highest resolution satellite images, or accuracy to the minute of the land use change in the imagery. In order to efficiently and effectively use the data gathered from satellites to identify deforestation non-compliances, several other aspects need to be taken into account.

1. Ownership

Knowledge of land or concession ownership and management oversight, as well as the accuracy of these boundary maps, are crucial when addressing information received related to deforestation and fires, among others. Without these reference points, further investigation, intervention or action related to deforestation alerts or data received from satellite monitoring platforms such as Global Forest Watch (GFW), Starling Verification or Kepo Hutan by Greenpeace cannot be carried out, regardless how precise the satellite imagery is.

Similarly, the ability to identify and engage with land owners or managers is essential when dealing with prevention, early detection or rapid response for fires outside of concession boundaries.

2. Baseline information related to previous land types and land-use change

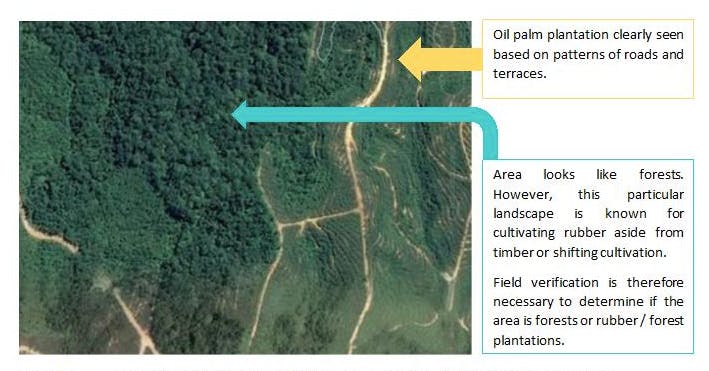

Viewing satellite images in retrospect can be challenging as past images are not necessarily in the best resolution or quality. It is crucial to be able to refer to or verify changes that have taken place in the affected area to gain the best insight, especially in areas with historical cultivation of agricultural crops such as rubber and cocoa, among others. Without verification as part of the process, a retrospective satellite image is essentially a photograph of the past. You can guess what it was like, but it is still a guess.

Image 1: Sample of a satellite imagery that requires ground verification for land-use changes.

Limitations of satellite technology

Satellite imagery has been an effective tool in monitoring deforestation for the palm oil industry, but as with all tools, there are limits to the technology. It is less effective in monitoring of new peatland development and unsuccessful in identifying issues related to exploitation or violations of human or labour rights.

Focusing on peatland development, satellite imagery has thus far not been able to penetrate or identify the varying soil layers to detect types of peat. Therefore, monitoring of peatland development must be supplemented with accompanying information from soil assessments as well as government-based gazettement of peat areas.

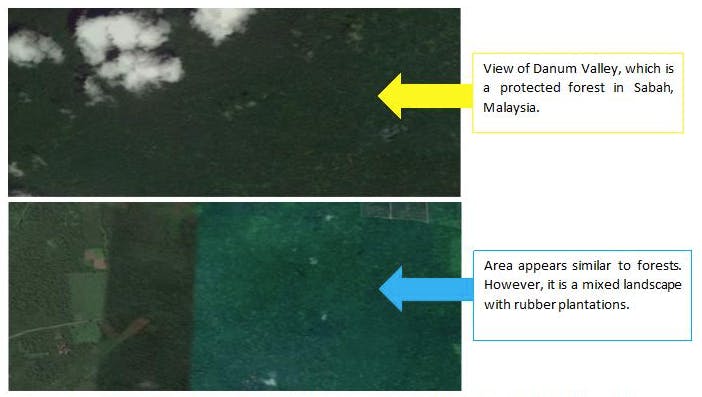

Image 2: Sample of a satellite imagery with poor resolution.

Limitations of private sector initiatives

Wilmar used satellite imagery to determine the impact of mills adjacent to deforestation-prone areas as part of our initial mill risk prioritisation efforts when publishing the list of all our supplying mills in 2015, which was the first such initiative in the palm oil industry. Identifying and understanding the types of risks and impacts around our supplying mills allowed us to determine the type of support required by our suppliers’ mills to further improve their own sustainability practices and requirements, including environmental compliance and labour conditions.

Image 3: Comparison between primary forests and mixed landscape with rubber plantations, which appear somewhat similar.

However, identifying land-use changes surrounding mills through satellite imagery could not translate to action or intervention if the deforestation occurred outside of the related mill’s boundaries of influence and control. This is especially more challenging when the land-use changes in question are not related to their own operations.

Among the primary challenges faced by private sector is that the targeted transformation of the supply chain towards more responsible and sustainable practices are confined by the presence of an existing or potential business relationship.

Removing non-compliant suppliers from our supply chain will ensure that we continue to be committed to our sustainability commitments. However, it also removes any influence that we have on these suppliers and therefore, disallowing us from guiding them towards transforming their existing practices to one that is more sustainable.

“

It is easy to use satellite imagery to continually blame the industry but it will not resolve any problems. What is needed is continual supplier engagement and ground verification and working on the factors driving deforestation outside our and our suppliers’ concessions.

Wilmar has excluded over one million metric tonnes of palm oil from our supply chain over the last five years due to non-compliance to our ‘No Deforestation, No Peat, No Exploitation’ (NDPE) policy. However, these same volumes have still managed to find its way into the larger palm oil markets through other actors who have lower or no sustainability commitments in place.

It is therefore vital that development, implementation and enforcement of government policies and regulations are also essential towards halting deforestation, aside from supporting forest conservation and protection efforts.

An unfortunate example is when the Brazilian government reversed its previous stand and related policies meant to tackle deforestation, therefore resulting in an expected increase in deforestation cases in the country. This was well documented in an article published by Mongabay on 25th June 2019, titled, ‘Satellite Data Suggests Deforestation on the Rise in Brazil’.

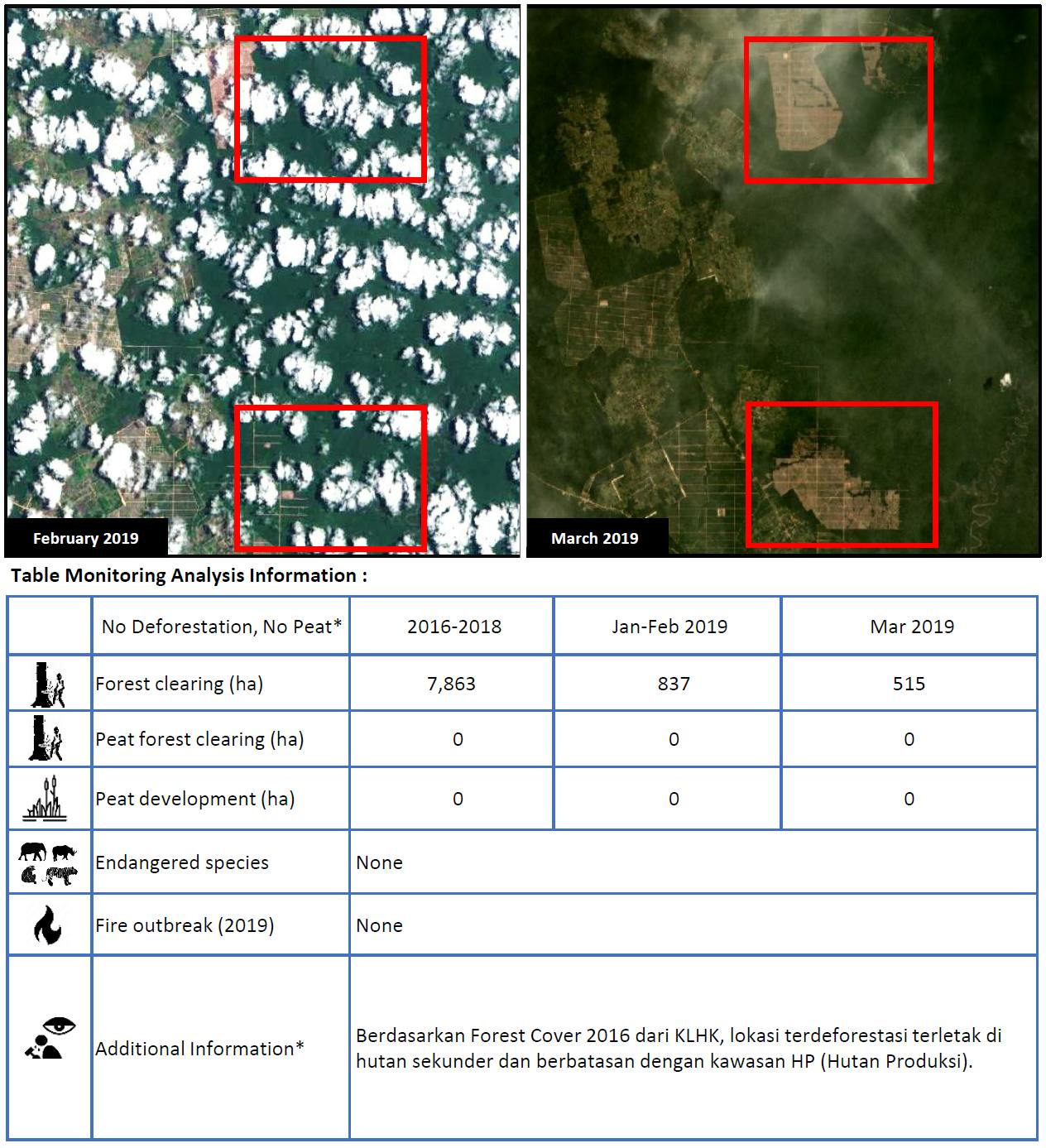

Continuing efforts in removing deforestation from our supply chain

Wilmar uses satellite imagery to proactively monitor its 30,000 hectares of conservation areas set-aside and also that of their suppliers. Working with Aidenvironment since 2014, and through their Supplier Group Compliance Programme (SGCP), Wilmar monitors over 14.75 million hectares associated with their supply chain. Wilmar also monitors satellite imageries Visible Infrared Imaging Radiometer Suite (VIIRS) and National Aeronautics and Space Administration (NASA) on a daily basis from for fire monitoring and management, which is especially crucial during dry seasons.

Wilmar launched their NDPE policy in December 2013, not too long before I joined them in 2014. They launched the NDPE policy with minimal pressure from non-governmental organisations (NGOs) at the time due to the belief that sustainability is Wilmar’s business model.

Having previously worked with the World Wide Fund for Nature (WWF) and the United Nations Development Programme (UNDP) on areas related to conservation, environment and sustainable development, I understood that Wilmar’s commitment was, and still is, a massive undertaking as it is applicable to their suppliers at group-level. However, it was this same commitment that assured me that I was joining not only a leading global agribusiness group, but also a frontrunner in sustainability in the palm oil industry.

Striving to transform the industry through Wilmar’s influence continues to be a challenge that we have to overcome, especially after January 2019 when Wilmar introduced more stringent requirements towards ensuring continued and greater compliance.

However, despite our best efforts, Wilmar continues to be the focus of campaigns against deforestation in the palm oil industry. It was demoralising for us in Wilmar, and to me personally, having been constantly singled out despite all our ongoing work to meet our sustainability commitments while other industry players with lesser or even no commitments continue to slip through the cracks.

Figure 1: Sample of a monitoring report received under Wilmar’s Supplier Group Compliance Program. The company is not in Wilmar’s supply chain.

Rising up to challenge, in December 2018, we rallied and persevered by reaffirming our commitment to break the link between oil palm cultivation with that of deforestation, peatland development and social conflict. Wilmar, together with Aidenvironment and supporting consumer goods companies, issued a joint statement detailing our new supplier monitoring and engagement programme, to really help deliver a deforestation-free palm oil supply chain.

It is easy to use satellite imagery to continually blame the industry but it will not resolve any problems. What is needed is continual supplier engagement and ground verification and working on the factors driving deforestation outside our and our suppliers’ concessions.

Ginny Ng is conservation advisor at global agribusiness firm Wilmar International.