Every development project – from factories and sports fields, to shopping malls and railways, will have a negative impact on the environment. Based on a sample of 5,300 large, publicly traded global companies, over 2,000 (38 per cent) have at least one facility associated with habitat loss, according to a report by Moody’s ESG Solutions published on Thursday.

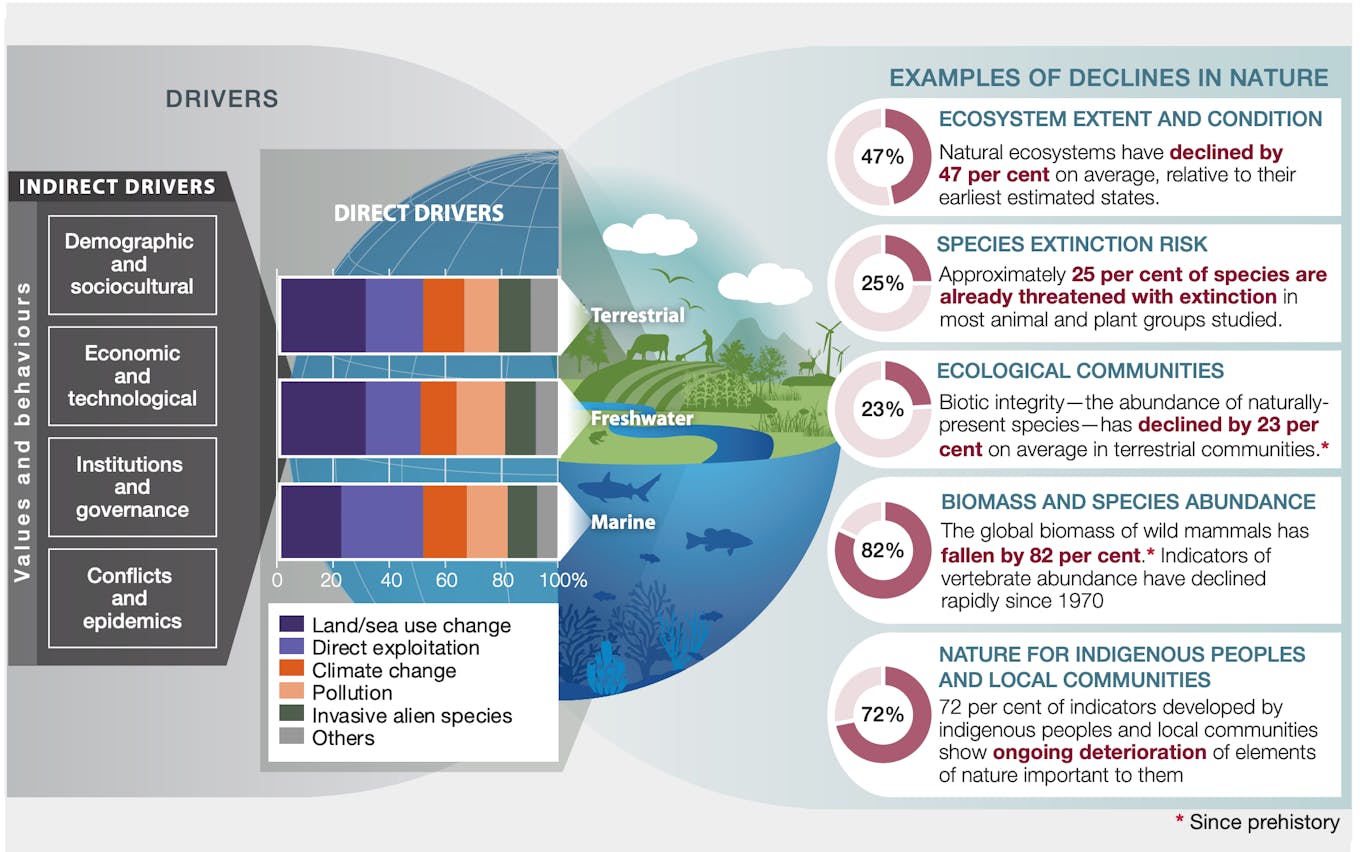

Biodiversity-related risks are rising up the agenda for companies, investors and policymakers as nature is declining at unprecedented rates. One million animal and plant species are at imminent risk of extinction due to humankind’s relentless pursuit of economic growth, according to a landmark report by the Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES).

Governments and the private sector are increasingly looking to counter biodiversity loss through instruments that are based on the “polluter pays” principle where the polluting party pays for the damage done to the natural environment.

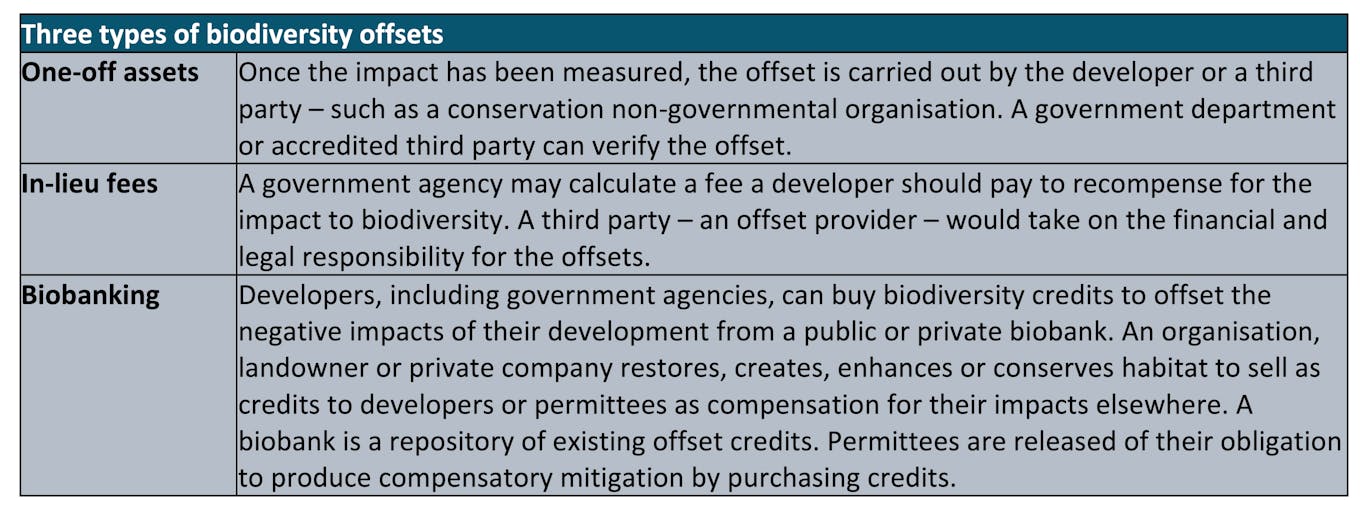

Biodiversity offsets are a measurable way for companies and governments to compensate for the impact of development projects by imposing a cost on the activities that cause adverse impacts to natural habitats. The offsets are based on the premise that impacts from development can be compensated – on the provision that sufficient habitat can be protected, enhanced or established elsewhere.

Source: OECD, United Nations Global Compact, International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

How does it work?

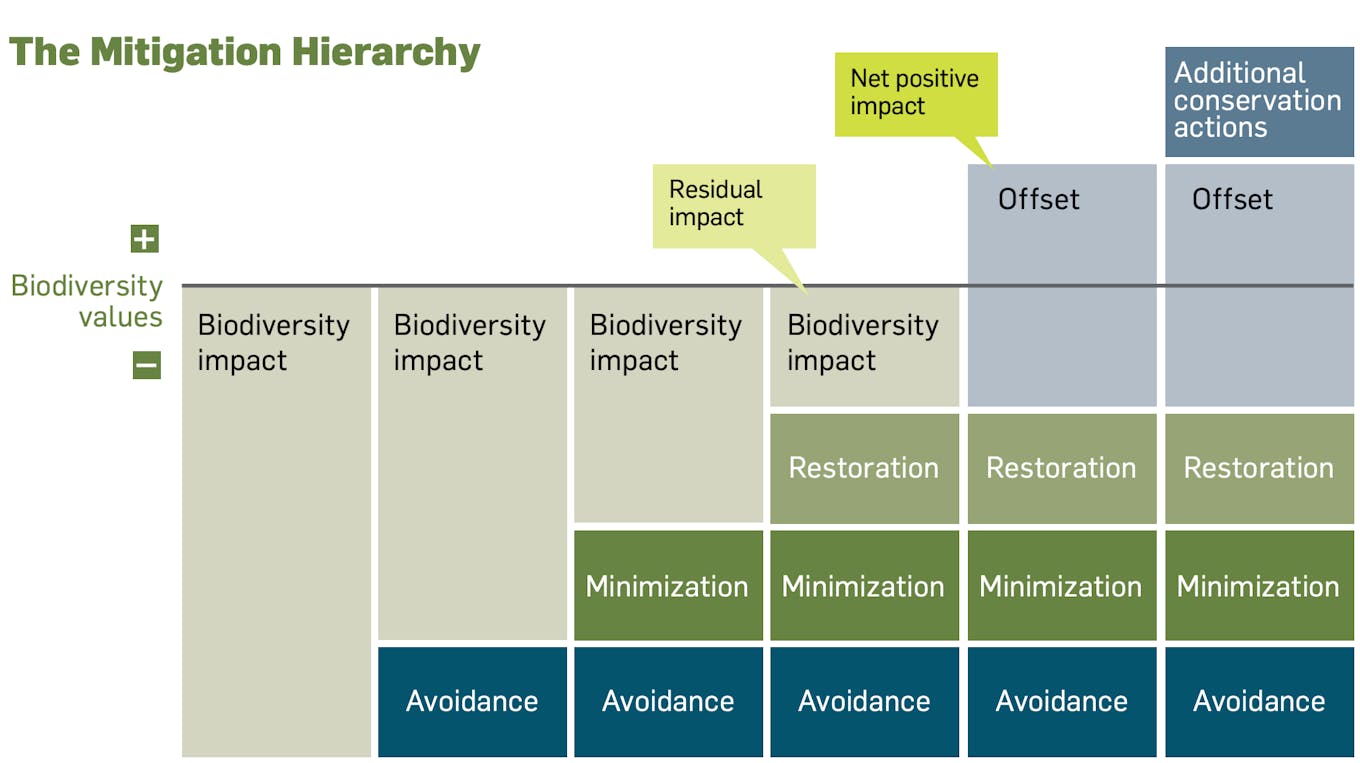

Biodiversity offsets should be the last resort and must only occur after all previous steps in a mitigation hierarchy in which impacts should be avoided if possible, mitigated for, if they cannot be avoided (through minimisation or on-site rehabilitation); lastly, any residual impacts should be compensated for through offsets.

Land, and the biodiversity on it, is assessed as having a value. Companies look to biodiversity offsets to achieve no-net-loss, meaning that ecological losses must be fully balanced by corresponding ecological gains produced by offsetting gains. Preferably, biodiversity offsets will result in a net gain.

“Biodiversity offsets must never be used to circumvent responsibilities to avoid and minimise damage to biodiversity, or to justify projects that would otherwise not happen,” according to a policy paper by the IUCN, a membership organisation which works in nature conservation and the sustainable use of resources.

Impacts on biodiversity would (ideally) be measured in standardised ways identified by a governing body, and these measures are used to decide on the size, content and position of offsets.

Source: A Framework for Corporate Action on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, United Nations Global Compact and IUCN, 2012

How do you to put a price on nature?

With difficulty. Pricing carbon seemed like an impossible task a decade or so ago, but is now part of an increasingly sophisticated and prolific marketplace. However, experts are still in a quandary about how to put a price tag on nature.

“Unlike carbon, the nature side has not had the same level of focus on how you measure it, and it kind of dropped off the agenda. We don’t have a tradeable biodiversity credit,” said Kavita Prakash-Mani, chief executive of the Mandai Nature Fund, which helps conservation efforts in Asia.

The Business and Biodiversity Offsets Programme made some progress until 2018, but there has been a lapse in any institutional authority taking it on more recently. A Strategic Plan for Biodiversity 2011-2020 spearheaded by the Convention on Biological Diversity expired last year and the principles and methods around biodiversity offsets are still being devised.

Financial institutions can leverage their position to influence how frameworks are formed around offsets, according to Steve Edwards, senior programme manager at IUCN. “The International Finance Corporation’s (IFC) performance standards, for instance, have been replicated and absorbed by other multilaterals,” he told Eco-Business.

Operational guidelines are also dependent on context. “Biodiversity will always be local. Fresh water, for example, is localised. You can’t put a global number to it. It is what it matters to you, and makes no difference for someone else,” Prakash-Mani told Eco-Business.

An international marketplace for trading biodiversity offsets is unrealistic in the current context, Edwards believes. Guaranteeing the quality and the permanence of offsets are aspects that can scupper both carbon and biodiversity mitigation efforts. “The complexity of biodiversity is far greater than the way we have been able to describe and conceptualise carbon offsets,” Edwards explained.

Shifting, not offsetting

Damage to biodiversity caused by development can, in some cases, be compensated by restoring or protecting habitats elsewhere, but first there has to be greater disclosure about the damage that is being done.

While biodiversity offsets are increasingly being used by governments and companies, an IUCN study found current efforts to mitigate impacts were proving insufficient to reduce biodiversity decline.

Moody’s also found a disconnect between most companies’ commitments and tangible measures to reduce their impact on biodiversity in its recent study. For example, 61 per cent of assessed companies in the heavy construction sector disclose commitments to address biodiversity, yet less than 10 per cent of the sector receives a ‘robust’ or ‘advanced’ score for implementation.

Cost shifting – the diversion of offset funds to existing conservation programmes – is also a risk. A biodiversity offset must provide a new contribution to conservation - so it must be additional to prevention and mitigation measures already in place.

Examples of global declines in nature, emphasising declines in biodiversity, that have been and are being caused by direct and indirect drivers of change. Source: The global assessment report on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services, Intergovernmental Panel on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), 2019.

Limits to offsets

Some things cannot be offset. Some developments might endanger previously non-threatened species to a higher threat level – such as vulnerable or critically endangered species. In other cases, the values that are lost are specific to a particular place and cannot be replicated or found elsewhere. If this is the case, this would probably mean that a project should not proceed in its current design, advises IUCN.

The use of biodiversity offsets has been criticised, because offsets may not be effective if they are not strictly regulated and because their use may provide a ‘licence’ to degrade the environment, notes The Dasgupta Review, a global review on the Economics of Biodiversity published in February.

“Biodiversity offsets can help reconcile development with conservation - but if they allow governments to renege on their existing commitments by stealth, biodiversity offsets could cause more harm than good,” James Watson, professor of conservation science at the University of Queensland said following the publication of his 2015 paper, ‘Stop misuse of biodiversity offsets.’

In theory, biodiversity offsets should deliver conservation outcomes for at least as long as the biodiversity loss persists at a development site, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). It is a difficult aspect to secure as land tenure, financial viability and incentives for land management are all needed to ensure there is permanence to a biodiversity offset.

Putting the brakes on destruction

Unless there is action taken to reduce the intensity of human drivers of biodiversity loss, “there will be a further acceleration in the global rate of species extinction,” says the IPBES Global Assessment.

Issues around offsetting - both carbon and biodiversity - are likely to become more difficult with a greater scarcity of land and an erosion of species.

“Where we can really offset the damage done to biodiversity is by driving behavioural change. This means trying to enhance conservation, not just by simply buying land and protecting it in some way, but changing the way people interact with biodiversity and introducing mechanims that protect species that are threatened,” Edwards said.