In tandem with the increase in coronavirus cases, cities across Southeast Asia could see a surge in medical waste that few have the capacity to deal with, warned the Asian Development Bank (ADB) as it urged governments to deal with the excess waste as soon as possible.

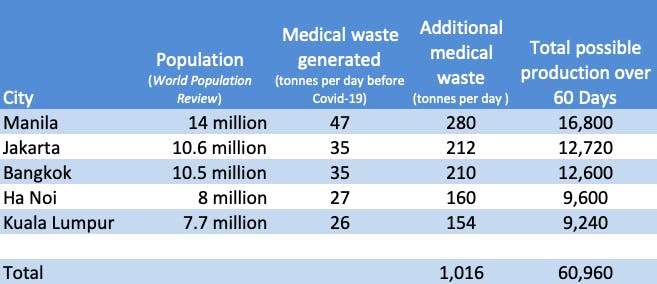

Calculating the extra waste that five of Southeast Asia’s largest cities could generate, based on the experience of China’s Hubei province—which saw infectious medical waste increase by six times to 240 tonnes a day—the ADB estimated that Manila, Jakarta, Bangkok, Kuala Lumpur and Hanoi could be dealing with a total of 1,016 tonnes more medical waste per day.

Seeing how the extra waste overwhelmed China’s medical transport and disposal infrastructure, the ADB said it was “critical that additional waste management systems are put in place to help reduce the further spread of Covid-19

and the emergence of other diseases”.

In a technical note titled Managing Infectious Medical Waste during the Covid-19 Pandemic posted on its website in April, the multi-lateral lender identified five major cities in the region which may not have the capacity to deal with the extra waste.

It estimated that hospitals in the Philippine capital of Manila, home to 14 million people and 37 per cent of those who have died from Covid-19 in the region as of 4 May, are expected to produce 280 tonnes of medical waste per day, compared with an estimated 47 tonnes generated daily before the epidemic occurred. Over a period of 60 days, the Philippine capital could be grappling with an extra 16,800 tonnes of medical waste.

“If you don’t dispose of medical waste urgently, this is the worst-case scenario that can happen, based on what happened in Wuhan. You will get overwhelmed and the most vulnerable people in your community are going to suffer the most,” Steve Peters, ADB’s senior energy specialist for waste-to-energy, and the technical note’s lead author, told Eco-Business.

However, Peters said incineration should be the last resort in disposing rubbish from treating coronavirus-positive patients. He recommended that governments collect and store the infectious medical waste temporarily in refrigerated shipping containers, in the event that it cannot be immediately disposed of. When the storage period ends, which is typically 60 to 90 days, the remaining waste may be brought to a cement kiln to be burned and turned into cement, just like what was done in China.

The high temperature, strong alkaline and high turbulent burning environment prevents the production of toxic fumes throughout the process, Peters said.

“

If you don’t dispose of medical waste urgently, this is the worst-case scenario that can happen, based on what happened in Wuhan. You will get overwhelmed and the most vulnerable people in your community are going to suffer the most.

Steve Peters, senior energy specialist for waste-to-energy, Asian Development Bank

Medical waste is typically sterilised by steam (autoclave) or irradiation prior to disposal in a licensed landfill, or incinerated.

One of the options is currently moot in the Philippines, where incineration is outlawed under the country’s Clean Air Act. But the Philippine department of environment and natural resources (DENR) has pushed for incineration as a mode of disposal, amid criticism from activists that it is a violation of the regulation.

However, Geri Sañez, chief of the department’s hazardous waste management section, said the activists’ interpretation of the incineration ban in the legislation is flawed.

“There is no absolute ban on incineration in the Philippines. The DENR can allow incineration processes that comply with standards including those for emissions,” Sañez told Eco-Business.

A chart in ADB’s Managing Infectious Medical Waste during the Covid-19 Pandemic shows that over a period of 60 days, Asian cities listed above could collectively churn out over 60,000 tonnes of medical waste. ADB noted that estimates are based on the experence in Wuhan, China. Other countries may experience different emergency timelines, which are dependent on specific policies and predicted infection curves, it said. Source: ADB Image: Eco-Business

According to the ADB’s estimates, Jakarta could generate 12,720 extra tonnes of used disposable gloves, gowns, face masks and intravenous therapy bags in 60 days during the height of the virus. The Indonesian city has seen the highest number of fatalities in the Asean bloc, accounting for about half the region’s coronavirus-related deaths as of 4 May.

Meanwhile, Bangkok could produce 12,600 extra tonnes of medical waste, with used face masks making up the bulk of the trash. The Thai metropolis has classified disposed face masks as hazardous waste, prompting city officials to deploy red rubbish bins to collect them, along with other infectious waste, to be incinerated at specialised facilities.

According to the ADB, governments can estimate the potential rise in volume of medical waste per day by multiplying the number of infected patients by 3.4 kilogrammes.

“

There is no absolute ban on incineration in the Philippines. The DENR can allow incineration processes that comply with standards including those for emissions.

Geri Sañez, chief of hazardous waste management section, Environmental Management Bureau, Department of Environment and Natural Resources

Environmentalists decry incineration as an option

Amid activists opposing the legality of waste incineration in the Philippines, Sañez cited a Supreme Court resolution that said not all incineration is prohibited, only burning processes which emit poisonous and toxic fumes.

Sañez said if Covid-19 related medical waste is incinerated, emissions of toxic fumes like dioxins and furans can be regulated by the Clean Air Act to ensure that the pollutants are within permitted limits.

Medical waste in the country is currently sterilised through thermal processing and pyroclave treatment which decomposes waste using extreme heat, then brought to the landfill.

“If the outbreak continues until end of the year, volume reduction of medical waste is needed. Other means of disposal like sterilisation will no longer be efficient because after the waste is disinfected, it goes to landfill which will not be able to accommodate that much waste as it competes with municipal waste,” he said.

Burning of Covid 19-related waste is already being done in Indonesia, as local laws allow it, said Aliansi Zero Waste Indonesia coordinator Abdul Ghofar.

But the government is pushing to maximise the combustion of medical waste to the full capacity of incinerators, even permitting unlicensed ones to be used as long as they have a minimum fuel temperature of 800°C, Ghofar added.

“We criticise the use of incinerators in handling Covid-19 waste and the use of unlicensed incinerators,” Ghofar told Eco-Business.

“Even the World Health Organisation (WHO) itself, in its long-term strategy, promotes the use of non-incinerator technology in handling medical waste. In fact Covid-19 can die with soap and heat of 100°C.”

In a 2014 publication on the safe management of waste, the WHO illustrated how sterilisation and disinfection of hazardous waste like autoclaving, microwaving, steam treatment integrated with internal mixing, and chemical treatment is more favourable than medical waste incineration.

“The WHO has reviewed small-scale health-care incinerators and reported significant problems regarding the siting, operation, maintenance and management of [these] incinerators. As a result of these and other concerns, together with the very high costs for modern incineration to meet best available technique standards, small-scale incineration is viewed as a transitional means of disposal for health care waste,” the guide stated.

The WHO further advised that prior to disposal, colour coding of hazardous waste makes it easier for medical staff and hospital workers to put waste items into the correct container. Infectious medical waste should be segregated by hospital staff at the time of packing, double-bagged and sprayed on the outside with 0.5 per cent chlorine solution before onsite temporary storage. The method of disposal then varies between hospitals, it said.