Indonesia’s forest products sector, dominated by pulp and paper companies, gets a third of its wood from illegal and unsustainable sources today. And even as some companies have made zero-deforestation pledges, there is simply not enough legally sourced wood to meet the demand, a new study has found.

In a new report launched on Tuesday, American non-profit Forest Trends and Indonesian group Anti Forest-Mafia Coalition revealed that 30 per cent of the wood used by forestry companies in Indonesia is illegal.

This unsustainable wood – which may come from the unreported clearing of natural forests and other illegal sources - amounts to about 20 million cubic metres of wood, or 1.5 million logging trucks, said the study, titled ‘Indonesia’s Legal Timber Supply Gap and Implications for Expansion of Milling Capacity’ .

And this is with mills not even operating at their full capacity. If companies speed up operations and go ahead with plans to open more mills, illegal wood could make up 59 per cent of the wood used if the industry does not increase its supply of legal wood, the report said.

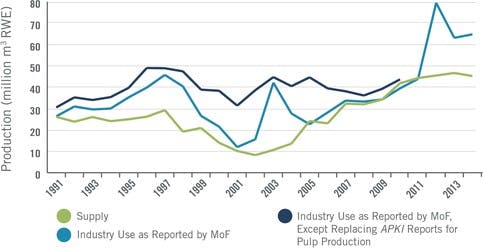

A comparison of reported timber use vs supply in Indonesia. Image: Forest Trends

Michael Jenkins, president and chief executive of Forest Trends, noted that “the timber industry’s own numbers show that Indonesia’s wood supply is unsustainable”.

Efforts by companies to scrub wood from natural rainforests from their supply chain – such as APP’s 2013 zero-deforestation pledge – are not a viable solution if the industry keeps expanding, said Jenkins.

The pulp sector today already does not have an adequate supply of plantation wood to meet its industrial capacity today. If companies make zero-deforestation pledges without halting expansion, “it would be impossible to meet current demand for timber”, said Jenkins.

The study based this finding on comparisons of the Indonesian Ministry of Forestry’s data on the available supply for wood against the volume of production reported by the industrial forestry sector.

It is unclear where the illegal wood that is currently used by mills comes from. But it is likely to be from trees harvested when forests are clear-cut to make way for new palm oil or paper plantations, suggested the report.

Indonesia has the dubious distinction of the world’s fastest rate of deforestation - in 2007, 2013 and 2014 - thanks to forest clearance by palm oil and agroforestry companies. The illegal ‘slash and burn’ method of forest clearance also causes haze pollution in Southeast Asia every year.

Feeding new mills sustainably

“

Instead of allowing for new mills to be built, it would be advisable for Indonesia to hold future expansion of the pulp and paper industry until they successfully increase the number of tree plantations.

Michael Jenkins, president and CEO, Forest Trends

The report also casted a wary eye on plans by Indonesian companies APP, Berito Pacific, Djarum PT, and Medco, which have invested more than US$12 billion in new mills in the provinces of South Sumatra, Kalimantan, and Papua. These new mills will widen the gap between demand for timber and available supply, said the authors.

“Instead of allowing for new mills to be built, it would be advisable for Indonesia to hold future expansion of the pulp and paper industry until they successfully increase the number of tree plantations,” suggested Jenkins.

Companies operating in the sector should publicly confirm that they can supply their mills with legally harvested wood before building new mills, he added.

The South Sumatra mill, owned by APP, is a US$2.6 billion project slated for completion in 2016. When completed it will be Indonesia’s largest mill and produce 2 million tonnes of pulp and 500,000 tonnes of tissue annually.

Responding to queries by Eco-Business, APP said that this demand will be met through only trees grown on plantations, as opposed to wood from natural forest.

The company in September underwent an audit by non-profit The Forest Trust, which confirmed that APP had enough plantation resources to meet the pulp requirements of its existing mills as well as its future mill in South Sumatra, provided it took steps to increase yield productivity and reduce waste.

In January, APP also received approval from green group Rainforest Alliance that it had successfully stopped the cutting of natural forests to make way for new plantations. This commitment to stop deforestation was a key element of the company’s 2013 Forest Conservation Policy.

Aida Greenbury, managing director of sustainability, APP, acknowledged that the legality of fibre was a serious problem for wood based industries, “which is why APP has gone to great lengths to tackle it”.

“APP is committed to Zero Deforestation through its Forest Conservation Policy and is 100 per cent plantation reliant for virgin fibre,” said Greenbury, adding that all APP mills had Indonesia’s required legality certification. All the wood entering APP mills is also independently monitored and verified, she said.

Commenting on the report, competitor company Asia Pacific Resources International Limited (APRIL) said that all its wood is from legal sources, and this can be verified through a chain of custody tracking system.

An APRIL spokesperson told Eco-Business that the company had finished establishing sustainable plantations at the end of last year, and has no pulp mill expansion plans. It is also working towards a commitment to conserve one hectare for every hectare of plantation.

APRIL has been criticised as the “greatest single threat facing Indonesia’s forests” by environmental campaigners Greenpeace. Reasons given for this include the fact that its pledge to source wood solely from plantations kicks in only in 2019. Greenpeace last month claimed that the company continued to drain ecologically important peatlands and clear rainforest as recently as last November.

In addition to a moratorium on new mills, the report also called for the sector to make improvements to its reporting practices, noting that timber use by small companies is under-reported, while public reports by pulp companies are not detailed enough. Some, like the Indonesia Pulp and Paper Association, stopped public reporting altogether since 2010.

Indonesia stands to lose more than just its forests

The lack of guaranteed legal wood from Indonesia’s forests outlined in the report could also threaten its economy, said the report. For instance, the country, which exports more than US$10 billion of forest products annually, in 2013 signed a trade agreement with the European Union to speed up the import of legal wood.

But this could be undermined if the industry cannot demonstrate that the timber used is legal. Not only would this harm exports, an inability to operate within the law would also make the Indonesian forestry industry less attractive to risk-conscious foreign investors, noted Jenkins.

“This report clearly underlines the extent to which the government of President Joko Widodo […] will face major obstacles in putting Indonesia on a path to sustainability,” he added.